Covid-19 plunged the global economy into its deepest crisis since the Great Depression. As more data emerges on the impact of the pandemic on labour markets, there is mounting international evidence that women have experienced more job (and income) losses than men - increasingly being referred to as the “shecession” - which has commonly been attributed to two main factors:

- firstly, that social distancing and travel restrictions have had greater impact on contact-intensive sectors, such as hospitality and tourism, where a higher proportion of women typically work; and

- secondly, that young women typically bear the greatest burden of domestic work and caring responsibilities, both of which have increased following widespread school and childcare closures and may reduce time available for paid work.

While these two factors are frequently cited, there is little evidence on their relative contribution to unequal employment recovery, especially in low- and middle-income countries.

Recent Young Lives research has tested whether – and to what extent - these two factors explain an increased gender employment gap and slower job recovery among young women during the second half of 2020. The paper focusses on the period following national lockdowns and associated Covid-19 restrictions, in three of our study counties: India (Andhra Pradesh and Telangana), Peru and Vietnam.

Our results show that unequal caring responsibilities have an important impact on the gender employment gap and slower job recovery for young women in Peru and Vietnam; accounting for up to 11% of the increased employment gap in Peru and 27% of the (relatively smaller) increase in Vietnam. Surprisingly, this factor appears to be less influential in India, explaining no more than 6% of the increased gender gap. In contrast, we found that working in a vulnerable economic activity was not a major factor in explaining gender differences in post-lockdown employment recovery in any of our three study countries.

The direct impact of increased caring responsibilities on the gender employment gap has important implications for national policy-makers and Covid-19 recovery plans. Aligning employment recovery schemes with improved measures to relieve the burden of increased caring responsibilities, such as local creche facilities, childcare support or cash benefits for families affected by childcare closures, could help to support young women getting back to work after lockdowns.

More research is needed to investigate other potential factors at play in explaining the difference between young women and men’s employment recovery; for example, whether men have more flexibility than women to switch employer or migrate for work in times of crisis.

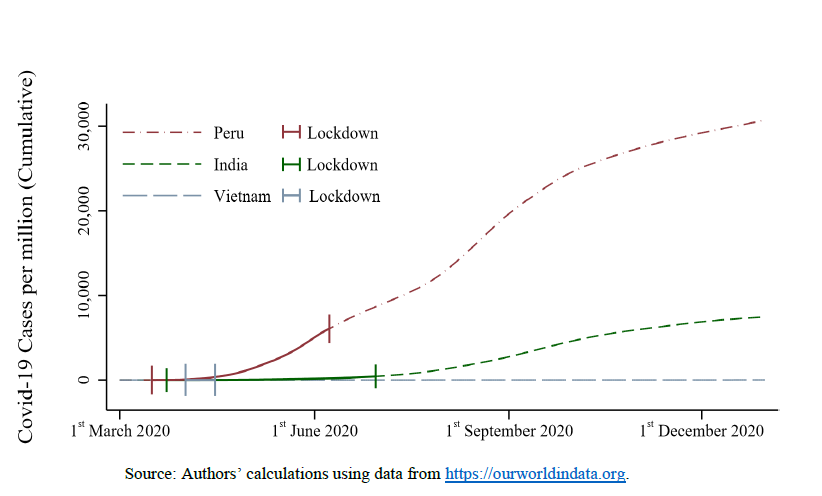

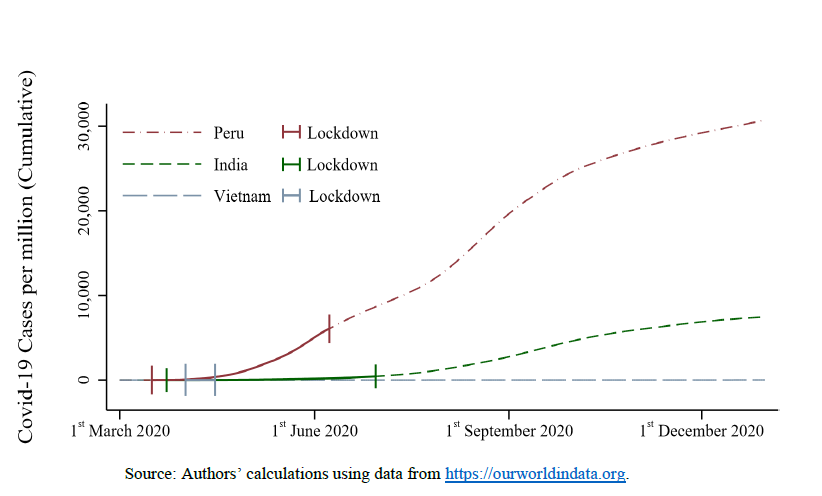

Our three study countries had very different experiences of the pandemic throughout 2020 (see Fig. 1). Peru suffered one of the highest per capita Covid-19 cases and death rates in the world, while Vietnam had one of the lowest.

Fig 1. Timeline of Covid-19 cases in India, Peru and Vietnam

National responses to the pandemic also varied throughout 2020. India implemented a 75-day national lockdown (from 23 March – 8 June 2020), during which only essential services were permitted to continue, while educational institutions were closed and remained closed throughout the year. In Peru, the national lockdown lasted 107 days (from 16 March - 30 June 2020), with the closure of educational and childcare institutions also continuing throughout 2020. In contrast, Vietnam implemented a relatively short 15-day national lockdown, from the 1st of April, though had already implemented a series of early measures, including school closures and restrictions on nonessential businesses. Following relative early success in containing the virus, schools in Vietnam began re-opening for face-to-face teaching in May 2020.

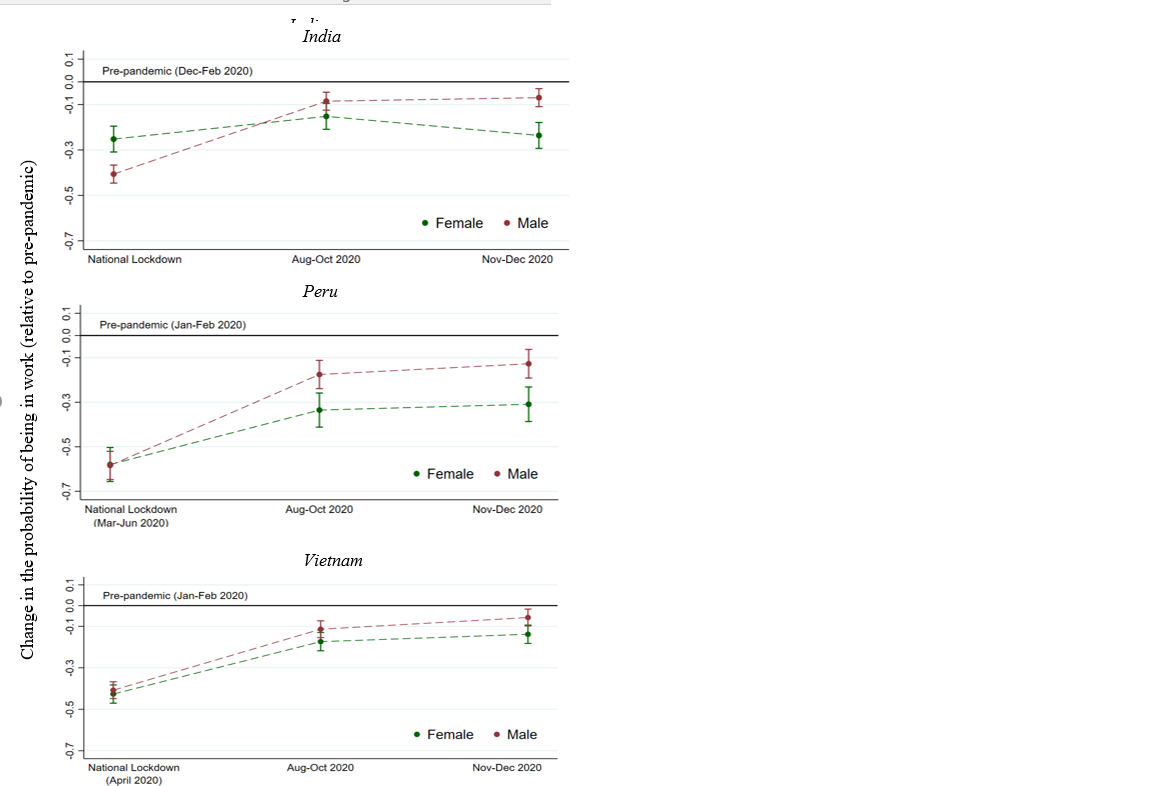

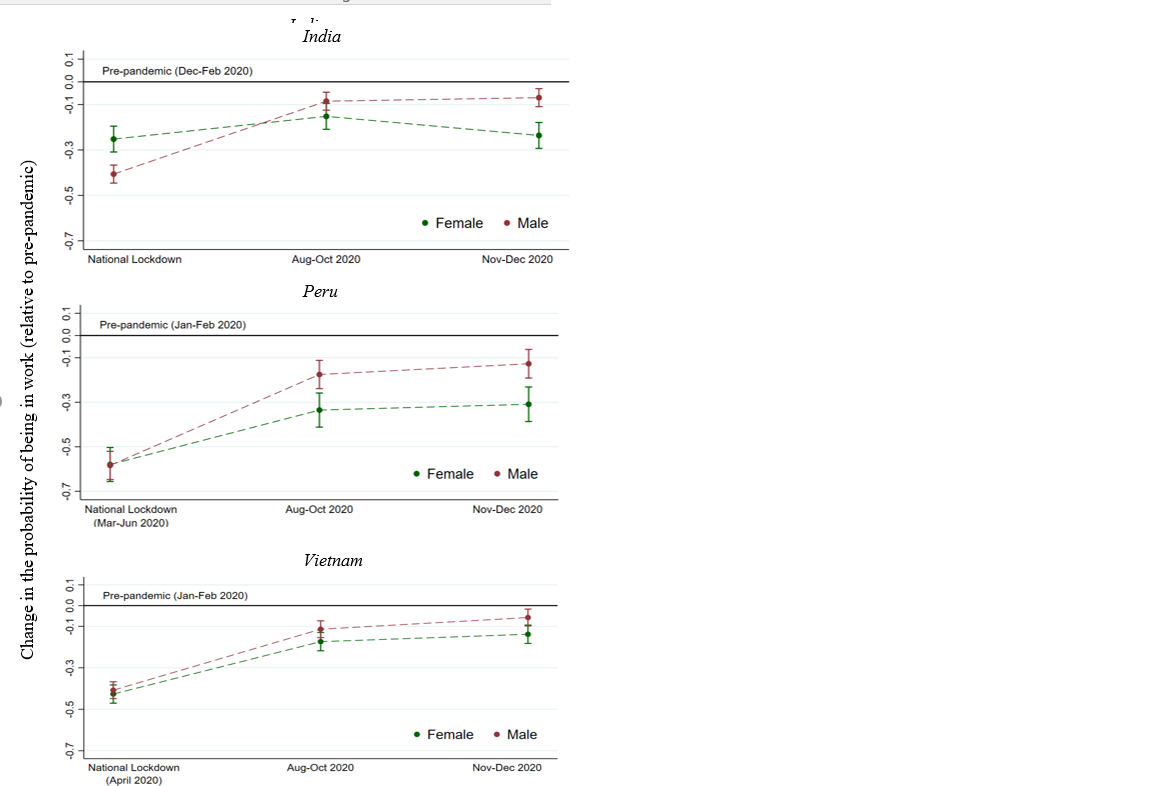

While young women’s employment appears not to have been disproportionately affected during national lockdowns, women who lost their jobs were significantly less likely to re-join the labour market after lockdowns ended, in all three study countries. As the months passed, gender differences in employment recovery increased through the second half of 2020; by November-December 2020, women who were employed before the pandemic were between 8 (Vietnam) and 18 percentage points (Peru) less likely to be back in employment than men (see Fig. 2).

Fig 2. Labour market recovery towards pre-pandemic levels

To measure the relative contribution of our two factors – pre-pandemic work activity and caring responsibilities - on unequal gender employment recovery, we used an analytical method called ‘mediation analysis’. First, for each time period, we estimated the probability of being employed, if the type of employment and level of caring responsibilities before the pandemic were the same for both men and women. By using these probabilities, we can calculate the theoretical gender employment gap if both factors were not able to differentially affect the probability of employment (called the ‘average controlled direct effects’ or ACDE). By subtracting the ACDE from the actual change in the gender employment gap, we are then able to measure the estimated proportion of the employment gap attributed to each factor.

We defined an individual’s caring responsibilities as whether the individual was required to look after children, old people, ill, disabled, or other household members who required special care. As expected, these responsibilities were heavily weighted towards young women in all countries, even before the pandemic. We defined a ‘vulnerable job’ as working (pre-pandemic) in one of the three economic activities which were worst affected by job losses during the national lockdowns (based on our data), which were typically contact-intensive sectors.

In Peru and Vietnam, we found that unequal household caring responsibilities explain a meaningful proportion of the gender-specific employment impact. This accounts for between 5% (August-October) and 11% (November-December) of the increase in the gender employment gap in Peru, and between 12% (August-October) and 27% (November-December) of the (relatively smaller) increase in Vietnam. Surprisingly, unequal caring responsibilities appear to be less influential in India, explaining no more than 6% of the increase in the gender employment gap in the Indian sample.

We also found that working in a vulnerable job was not a major factor in explaining gender differences in post-lockdown employment recovery in any of the three countries. Being employed in a work activity where job losses were high during the lockdowns accounted for, at most, just over 1% of the change in the gender employment gap (in Peru in August-October), with the additional risk of being out of work affecting both young women and young men.

In all countries, we also found that a large share of the post-lockdown employment gap cannot be attributed to either of the two commonly suggested factors, posing the question of what other factors may be in play? While more research is needed, we found tentative evidence that a higher flexibility for males to i) switch activity or employer and/or ii) migrate for work, may explain some of the remaining gender gap in employment outcomes.

Young Lives research provides robust evidence on the impact of caring responsibilities on unequal employment recovery in 2020, with important policy implications. Aligning employment recovery schemes with improved measures to relieve the pressure of increased childcare, such as local creche facilities, childcare support or cash benefits for families affected by childcare closures, could help to support young women getting back to work. Even before the Covid-19 pandemic, evidence suggested that women’s employment may be especially sensitive to measures that help alleviate these types of pressures.

The closure of schools and childcare facilities will inevitably have left many women with increased responsibilities that cannot easily be balanced with work, whether this is caring for their own children or others within the household. Many of the young women in our study are also entering a critical transition period into marriage and motherhood, potentially making labour market re-entry even more difficult.

The data on which these findings are based comes from a three-part Covid-19 phone survey, conducted by Young Lives between June and December 2020. The survey interviewed nearly 10,000 young people from two cohorts aged 19 and 26, in Ethiopia, India (Andhra Pradesh and Telegana), Peru and Vietnam. These individuals have been part of our longitudinal study since 2001. The information used to generate our results on the gender employment gap was taken from the second and third phone calls, which took place between August-October and November-December 2020, respectively. We did not use data from our Ethiopian sample in this analysis, as there was no national lockdown imposed there in 2020.

As all three countries continue to struggle with successive waves of the pandemic and vaccination rates lag behind those of high-income countries, there have been further social and economic restrictions during 2021, with further restrictions likely in the future.

Young Lives has, therefore, extended this phone survey, with a short fourth call completed in August, and a more comprehensive fifth call completed in October-December 2021, which is due to report findings in early March 2022. These findings will further investigate the labour market recovery for young women and whether the gender employment gap has continued to increase during 2021, or has reverted back to pre-pandemic levels.

Covid-19 plunged the global economy into its deepest crisis since the Great Depression. As more data emerges on the impact of the pandemic on labour markets, there is mounting international evidence that women have experienced more job (and income) losses than men - increasingly being referred to as the “shecession” - which has commonly been attributed to two main factors:

- firstly, that social distancing and travel restrictions have had greater impact on contact-intensive sectors, such as hospitality and tourism, where a higher proportion of women typically work; and

- secondly, that young women typically bear the greatest burden of domestic work and caring responsibilities, both of which have increased following widespread school and childcare closures and may reduce time available for paid work.

While these two factors are frequently cited, there is little evidence on their relative contribution to unequal employment recovery, especially in low- and middle-income countries.

Recent Young Lives research has tested whether – and to what extent - these two factors explain an increased gender employment gap and slower job recovery among young women during the second half of 2020. The paper focusses on the period following national lockdowns and associated Covid-19 restrictions, in three of our study counties: India (Andhra Pradesh and Telangana), Peru and Vietnam.

Our results show that unequal caring responsibilities have an important impact on the gender employment gap and slower job recovery for young women in Peru and Vietnam; accounting for up to 11% of the increased employment gap in Peru and 27% of the (relatively smaller) increase in Vietnam. Surprisingly, this factor appears to be less influential in India, explaining no more than 6% of the increased gender gap. In contrast, we found that working in a vulnerable economic activity was not a major factor in explaining gender differences in post-lockdown employment recovery in any of our three study countries.

The direct impact of increased caring responsibilities on the gender employment gap has important implications for national policy-makers and Covid-19 recovery plans. Aligning employment recovery schemes with improved measures to relieve the burden of increased caring responsibilities, such as local creche facilities, childcare support or cash benefits for families affected by childcare closures, could help to support young women getting back to work after lockdowns.

More research is needed to investigate other potential factors at play in explaining the difference between young women and men’s employment recovery; for example, whether men have more flexibility than women to switch employer or migrate for work in times of crisis.

Our three study countries had very different experiences of the pandemic throughout 2020 (see Fig. 1). Peru suffered one of the highest per capita Covid-19 cases and death rates in the world, while Vietnam had one of the lowest.

Fig 1. Timeline of Covid-19 cases in India, Peru and Vietnam

National responses to the pandemic also varied throughout 2020. India implemented a 75-day national lockdown (from 23 March – 8 June 2020), during which only essential services were permitted to continue, while educational institutions were closed and remained closed throughout the year. In Peru, the national lockdown lasted 107 days (from 16 March - 30 June 2020), with the closure of educational and childcare institutions also continuing throughout 2020. In contrast, Vietnam implemented a relatively short 15-day national lockdown, from the 1st of April, though had already implemented a series of early measures, including school closures and restrictions on nonessential businesses. Following relative early success in containing the virus, schools in Vietnam began re-opening for face-to-face teaching in May 2020.

While young women’s employment appears not to have been disproportionately affected during national lockdowns, women who lost their jobs were significantly less likely to re-join the labour market after lockdowns ended, in all three study countries. As the months passed, gender differences in employment recovery increased through the second half of 2020; by November-December 2020, women who were employed before the pandemic were between 8 (Vietnam) and 18 percentage points (Peru) less likely to be back in employment than men (see Fig. 2).

Fig 2. Labour market recovery towards pre-pandemic levels

To measure the relative contribution of our two factors – pre-pandemic work activity and caring responsibilities - on unequal gender employment recovery, we used an analytical method called ‘mediation analysis’. First, for each time period, we estimated the probability of being employed, if the type of employment and level of caring responsibilities before the pandemic were the same for both men and women. By using these probabilities, we can calculate the theoretical gender employment gap if both factors were not able to differentially affect the probability of employment (called the ‘average controlled direct effects’ or ACDE). By subtracting the ACDE from the actual change in the gender employment gap, we are then able to measure the estimated proportion of the employment gap attributed to each factor.

We defined an individual’s caring responsibilities as whether the individual was required to look after children, old people, ill, disabled, or other household members who required special care. As expected, these responsibilities were heavily weighted towards young women in all countries, even before the pandemic. We defined a ‘vulnerable job’ as working (pre-pandemic) in one of the three economic activities which were worst affected by job losses during the national lockdowns (based on our data), which were typically contact-intensive sectors.

In Peru and Vietnam, we found that unequal household caring responsibilities explain a meaningful proportion of the gender-specific employment impact. This accounts for between 5% (August-October) and 11% (November-December) of the increase in the gender employment gap in Peru, and between 12% (August-October) and 27% (November-December) of the (relatively smaller) increase in Vietnam. Surprisingly, unequal caring responsibilities appear to be less influential in India, explaining no more than 6% of the increase in the gender employment gap in the Indian sample.

We also found that working in a vulnerable job was not a major factor in explaining gender differences in post-lockdown employment recovery in any of the three countries. Being employed in a work activity where job losses were high during the lockdowns accounted for, at most, just over 1% of the change in the gender employment gap (in Peru in August-October), with the additional risk of being out of work affecting both young women and young men.

In all countries, we also found that a large share of the post-lockdown employment gap cannot be attributed to either of the two commonly suggested factors, posing the question of what other factors may be in play? While more research is needed, we found tentative evidence that a higher flexibility for males to i) switch activity or employer and/or ii) migrate for work, may explain some of the remaining gender gap in employment outcomes.

Young Lives research provides robust evidence on the impact of caring responsibilities on unequal employment recovery in 2020, with important policy implications. Aligning employment recovery schemes with improved measures to relieve the pressure of increased childcare, such as local creche facilities, childcare support or cash benefits for families affected by childcare closures, could help to support young women getting back to work. Even before the Covid-19 pandemic, evidence suggested that women’s employment may be especially sensitive to measures that help alleviate these types of pressures.

The closure of schools and childcare facilities will inevitably have left many women with increased responsibilities that cannot easily be balanced with work, whether this is caring for their own children or others within the household. Many of the young women in our study are also entering a critical transition period into marriage and motherhood, potentially making labour market re-entry even more difficult.

The data on which these findings are based comes from a three-part Covid-19 phone survey, conducted by Young Lives between June and December 2020. The survey interviewed nearly 10,000 young people from two cohorts aged 19 and 26, in Ethiopia, India (Andhra Pradesh and Telegana), Peru and Vietnam. These individuals have been part of our longitudinal study since 2001. The information used to generate our results on the gender employment gap was taken from the second and third phone calls, which took place between August-October and November-December 2020, respectively. We did not use data from our Ethiopian sample in this analysis, as there was no national lockdown imposed there in 2020.

As all three countries continue to struggle with successive waves of the pandemic and vaccination rates lag behind those of high-income countries, there have been further social and economic restrictions during 2021, with further restrictions likely in the future.

Young Lives has, therefore, extended this phone survey, with a short fourth call completed in August, and a more comprehensive fifth call completed in October-December 2021, which is due to report findings in early March 2022. These findings will further investigate the labour market recovery for young women and whether the gender employment gap has continued to increase during 2021, or has reverted back to pre-pandemic levels.