“Is it a boy or a girl?” In many cultures, this is often the first question people ask when they find out that someone is having a baby. And so begins the process of gender socialization, intensifying during adolescence and continuing throughout our lives.

What is gender socialization?

In a discussion paper completed in collaboration between the UNICEF Office of Research-Innocenti and the International Centre for Research on Women (ICRW), gender socialization is defined as a “process by which individuals develop, refine and learn to ‘do’ gender through internalizing gender norms and roles as they interact with key agents of socialization, such as their family, social networks and other social institutions” (John et al., forthcoming 2016).

Why does it matter?

Gender norms around what constitutes appropriate behaviour for girls and boys are some of the most influential contributors to gender inequality. For example, in a number of contexts girls are expected to marry early and and have children during adolescence, resulting in fewer opportunities to attend school and work, poorer hecan lead to involvement in risky behaviours and conflict, bringing about negative consequences such as car accidents, substance abuse and death.

With the onset of puberty and ensuing expectations around gender roles, the process of gender socialization intensifies during adolescence, making it a critical period and a “second window” of opportunity for (re)shaping attitudes and behaviours that lead to more positive he

What will be covered at the Young Lives conference?

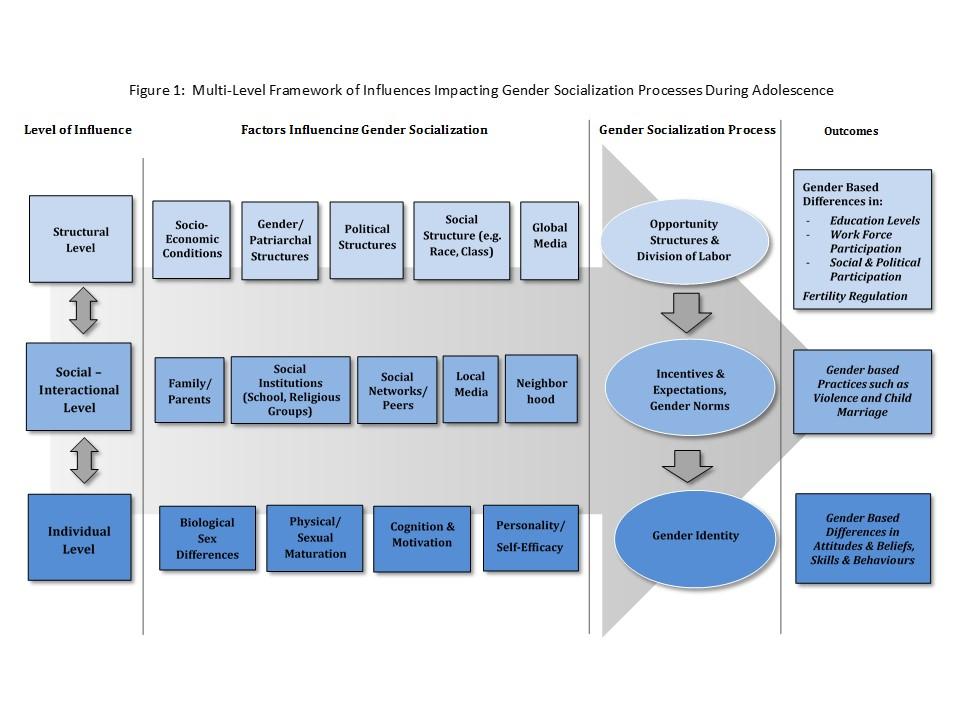

UNICEF is examining the process of gender socialization to better understand key entry points for programming and policy interventions to achieve more positive outcomes for adolescents in low- and middle- income countries. The forthcoming panel at the Young Lives conference on 9 September is a part of this objective. Titled ‘Influencing Gender Socialisation in Adolescence’, the panel aims to examine different structural and social influences of the gender socialization process and engage in a discussion around effective entry-points for intervening. The panel’s conceptual grounding is in the newly developed theoretical framework by ICRW, summarised in Figure 1 (John et al., forthcoming 2016). The framework is based on various theories from psychology, sociology and biology that pertain to the gender socialization process and a rapid review of interventions and outcomes at the individual, social-interactional and structural levels.

Figure 1: Multi-level framework of influences impacting gender socialization processes during adolescence. From John et al. (forthcoming 2016)

After a theoretical overview of the topic by Neetu John from ICRW, the panel will provide three empirical examples of how gender socialization is influenced in practice. The three studies demonstrate a combination of interventions targeting adolescents directly and indirectly through influential agents such as teachers, household heads and peers. They range from interpersonal approaches to those that are community and national level programmes, spanning several disciplines (education, peace-building, social policy and economics) and countries (India, Kenya, Malawi, Tanzania, Uganada, Zambia and Zimbabwe).

The first study by Chinen and colleagues’ from the American Institutes for Research – conducted in collaboration with the Gender unit at UNICEF headquarters, UNICEF Uganda and the Ugandan Ministry of Education, Science, Technology and Sports (MoESTS) – focuses on changing gender attitudes and behaviours in the impoverished, remote region of Karamoja, Uganda, where cultural norms, marginalization, and inadequate infrastructure aggravate the problem of gender inequality. Using teachers as “agents of change” in the gender socialization of children and very young adolescents, the eight-month programme consisted of teacher training in issues of gender equality and the reinforcement of positive gender socialization via SMS and was evaluated using a cluster-randomized control trial.

Recognizing that the process of gender socialization influences both boys and girls and that men and boys must be an integral part of efforts to promote gender equality, in the second study being presented, Ravi Verma and Abhishek Gautam from ICRW will present research from seven states in India, showing that masculinity – i.e. men’s controlling behaviour and gender inequitable attitudes – strongly determines men’s preference for sons over daughters. They will examine the factors that influence this relationship including social status, economic burden, and religious beliefs, and how they manifest in gender inequality and intimate partner violence.

Finally, adopting a different approach to how the process of gender socialization can be influenced by national programmes, Tia Palermo from the Office of Research-Innocenti will discuss evidence of changes in gender related outcomes from multi-country evaluations of cash transfers in Sub-Saharan Africa. The emerging evidence demonstrates that government cash transfer programmes have facilitated safe transitions during adolescence by delaying sexual debut and pregnancy, while preliminary evidence suggests that cash transfers may reduce sexual violence and transactional sex. Although not directly designed to influence gender equality, the impacts from cash transfers suggest they may be a promising approach in this area.

Ending with an engaging discussion

We look forward to a final discussion – facilitated by UNICEF’s Principal Adviser on Gender, Anju Malhotra – that critically examines the framework and evidence presented, reflecting not only on “what works, for whom and under what circumstances”, but also how to best include a gender component in effective programmes that don’t necessarily include gender equality as a specified objective.

Further Reading

John N. A., Stoebenau, K., Ritter, S., & J. Edmeades (forthcoming 2016). Gender Socialization during Adolescence in Low and Middle Income Countries: Background Paper on the Conceptualization, Influences and Outcomes of Gender Socialization. Innocenti Discussion Paper, UNICEF.

Kato-Wallace, J., Barker, G., Sharafi, L., Mora, L., Lauro, G. (2016). Adolescent boys and young men: Engaging Them as Supporters of Gender Equality and Health and Understanding their Vulnerabilities. Washington, D.C.: Promundo US. New York City: UNFPA.

UNICEF (2012). Progress for Children: A Report Card on Adolescents.

Nikola Balvin, PsyD, is a Knowledge Management Specialist at UNICEF Office of Research-Innocenti in Florence, Italy.

“Is it a boy or a girl?” In many cultures, this is often the first question people ask when they find out that someone is having a baby. And so begins the process of gender socialization, intensifying during adolescence and continuing throughout our lives.

What is gender socialization?

In a discussion paper completed in collaboration between the UNICEF Office of Research-Innocenti and the International Centre for Research on Women (ICRW), gender socialization is defined as a “process by which individuals develop, refine and learn to ‘do’ gender through internalizing gender norms and roles as they interact with key agents of socialization, such as their family, social networks and other social institutions” (John et al., forthcoming 2016).

Why does it matter?

Gender norms around what constitutes appropriate behaviour for girls and boys are some of the most influential contributors to gender inequality. For example, in a number of contexts girls are expected to marry early and and have children during adolescence, resulting in fewer opportunities to attend school and work, poorer hecan lead to involvement in risky behaviours and conflict, bringing about negative consequences such as car accidents, substance abuse and death.

With the onset of puberty and ensuing expectations around gender roles, the process of gender socialization intensifies during adolescence, making it a critical period and a “second window” of opportunity for (re)shaping attitudes and behaviours that lead to more positive he

What will be covered at the Young Lives conference?

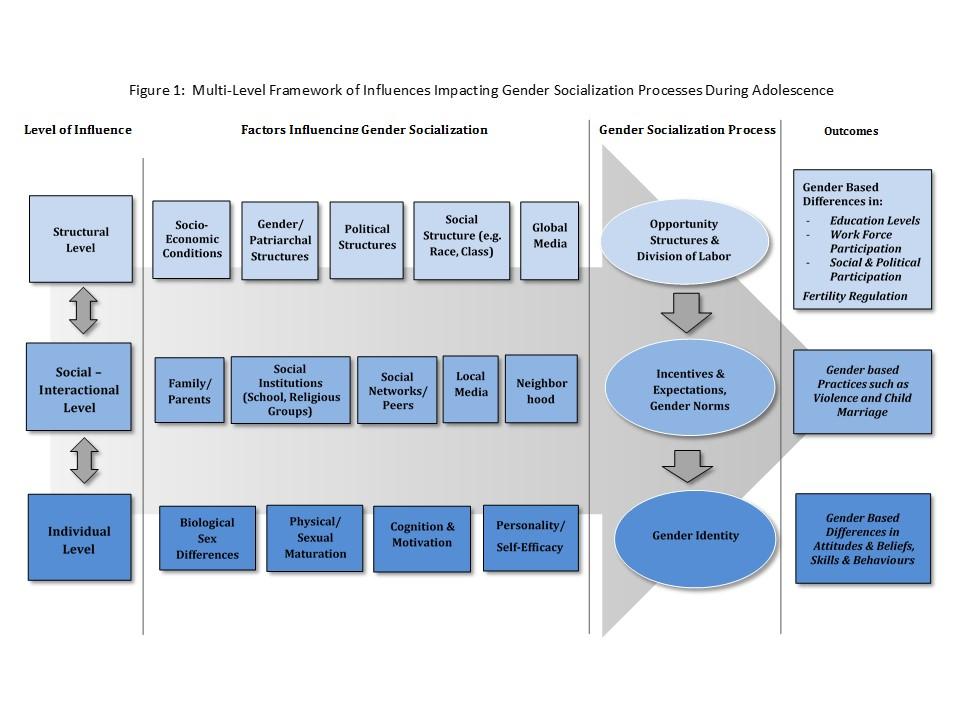

UNICEF is examining the process of gender socialization to better understand key entry points for programming and policy interventions to achieve more positive outcomes for adolescents in low- and middle- income countries. The forthcoming panel at the Young Lives conference on 9 September is a part of this objective. Titled ‘Influencing Gender Socialisation in Adolescence’, the panel aims to examine different structural and social influences of the gender socialization process and engage in a discussion around effective entry-points for intervening. The panel’s conceptual grounding is in the newly developed theoretical framework by ICRW, summarised in Figure 1 (John et al., forthcoming 2016). The framework is based on various theories from psychology, sociology and biology that pertain to the gender socialization process and a rapid review of interventions and outcomes at the individual, social-interactional and structural levels.

Figure 1: Multi-level framework of influences impacting gender socialization processes during adolescence. From John et al. (forthcoming 2016)

After a theoretical overview of the topic by Neetu John from ICRW, the panel will provide three empirical examples of how gender socialization is influenced in practice. The three studies demonstrate a combination of interventions targeting adolescents directly and indirectly through influential agents such as teachers, household heads and peers. They range from interpersonal approaches to those that are community and national level programmes, spanning several disciplines (education, peace-building, social policy and economics) and countries (India, Kenya, Malawi, Tanzania, Uganada, Zambia and Zimbabwe).

The first study by Chinen and colleagues’ from the American Institutes for Research – conducted in collaboration with the Gender unit at UNICEF headquarters, UNICEF Uganda and the Ugandan Ministry of Education, Science, Technology and Sports (MoESTS) – focuses on changing gender attitudes and behaviours in the impoverished, remote region of Karamoja, Uganda, where cultural norms, marginalization, and inadequate infrastructure aggravate the problem of gender inequality. Using teachers as “agents of change” in the gender socialization of children and very young adolescents, the eight-month programme consisted of teacher training in issues of gender equality and the reinforcement of positive gender socialization via SMS and was evaluated using a cluster-randomized control trial.

Recognizing that the process of gender socialization influences both boys and girls and that men and boys must be an integral part of efforts to promote gender equality, in the second study being presented, Ravi Verma and Abhishek Gautam from ICRW will present research from seven states in India, showing that masculinity – i.e. men’s controlling behaviour and gender inequitable attitudes – strongly determines men’s preference for sons over daughters. They will examine the factors that influence this relationship including social status, economic burden, and religious beliefs, and how they manifest in gender inequality and intimate partner violence.

Finally, adopting a different approach to how the process of gender socialization can be influenced by national programmes, Tia Palermo from the Office of Research-Innocenti will discuss evidence of changes in gender related outcomes from multi-country evaluations of cash transfers in Sub-Saharan Africa. The emerging evidence demonstrates that government cash transfer programmes have facilitated safe transitions during adolescence by delaying sexual debut and pregnancy, while preliminary evidence suggests that cash transfers may reduce sexual violence and transactional sex. Although not directly designed to influence gender equality, the impacts from cash transfers suggest they may be a promising approach in this area.

Ending with an engaging discussion

We look forward to a final discussion – facilitated by UNICEF’s Principal Adviser on Gender, Anju Malhotra – that critically examines the framework and evidence presented, reflecting not only on “what works, for whom and under what circumstances”, but also how to best include a gender component in effective programmes that don’t necessarily include gender equality as a specified objective.

Further Reading

John N. A., Stoebenau, K., Ritter, S., & J. Edmeades (forthcoming 2016). Gender Socialization during Adolescence in Low and Middle Income Countries: Background Paper on the Conceptualization, Influences and Outcomes of Gender Socialization. Innocenti Discussion Paper, UNICEF.

Kato-Wallace, J., Barker, G., Sharafi, L., Mora, L., Lauro, G. (2016). Adolescent boys and young men: Engaging Them as Supporters of Gender Equality and Health and Understanding their Vulnerabilities. Washington, D.C.: Promundo US. New York City: UNFPA.

UNICEF (2012). Progress for Children: A Report Card on Adolescents.

Nikola Balvin, PsyD, is a Knowledge Management Specialist at UNICEF Office of Research-Innocenti in Florence, Italy.