The new Young Lives research and policy findings on early marriage and teenage pregnancy launched in India this week have important implications for education, particularly for girls and their access to secondary schooling.

In light of my own research interests in gender, sexuality and education in India, this week’s reports encouraged me to explore Young Lives’ wider findings on gender and education more closely. This post is an attempt to briefly summarise the evidence from Young Lives on gender and education, both in terms of girls’ marginalisation in education, and the study’s findings which indicate that we must think more broadly about gender and education – for example, by considering educational disadvantage linked to intersections between gender, poverty status, language, ethnicity, caste, and geographical location.

Girls’ marginalisation in education

Within the Young Lives sample in Andhra Pradesh and Telangana, India, girls are significantly less likely than boys to complete secondary education; only 66% of girls progress through secondary school, compared to 77% of boys. Findings from Young Lives qualitative research highlight many reasons for girls being marginalised in and excluded from secondary education, including distance to school, inadequate safety, and engagement in paid and unpaid labour, particularly after they attain puberty. These issues particularly affect girls from scheduled caste, scheduled tribe and ‘backward caste’ families.

The latest findings from Young Lives indicate that leaving school early is a powerful predictor of child marriage and early childbearing in India. In Andhra Pradesh and Telangana, girls in the Young Lives Older Cohort who left school by age 15 were four times more likely to marry before age 18 than girls who were still enrolled. These girls were also more likely to come from poorer households, and their parents and caregivers were less likely to be well-educated or to have high aspirations for their daughters. These findings indicate the importance of safe, accessible and high-quality secondary education for girls, as well as the need for effective social protection and investment in livelihoods and opportunities for young women and men, so families feel confident that they can delay their daughters’ marriage and invest in their education and future.

Child marriage also has implications for girls’ education in Ethiopia. Within the Young Lives Older Cohort, girls in rural Ethiopia are much more likely to marry than girls in cities, with 21% in rural areas married before the age of 18, compared to 3% in urban areas. In a context of few other opportunities, where girls’ education is limited and there are restricted chances of training or employment, early marriage may be viewed as a rational option by parents and sometimes by girls themselves. Early marriage is also often perceived as a ‘safe’ choice - in Young Lives sites many parents expressed anxieties about girls going to secondary schools far away from home, where they were perceived to be at greater risk of abduction or rape. However, education itself has also become an important force for change in reducing early marriage in Ethiopia, along with greater employment opportunities and higher aspirations of girls and their families.

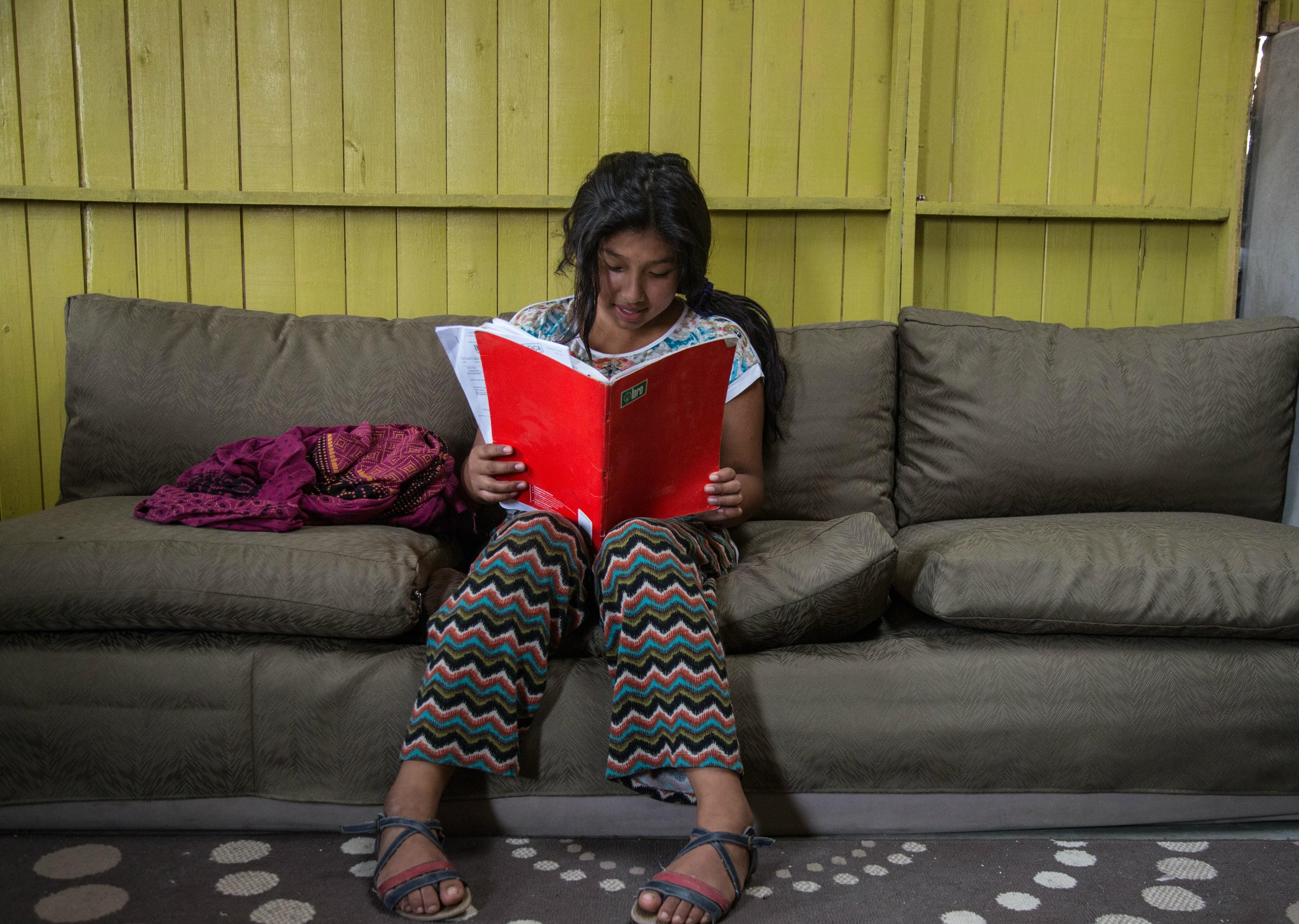

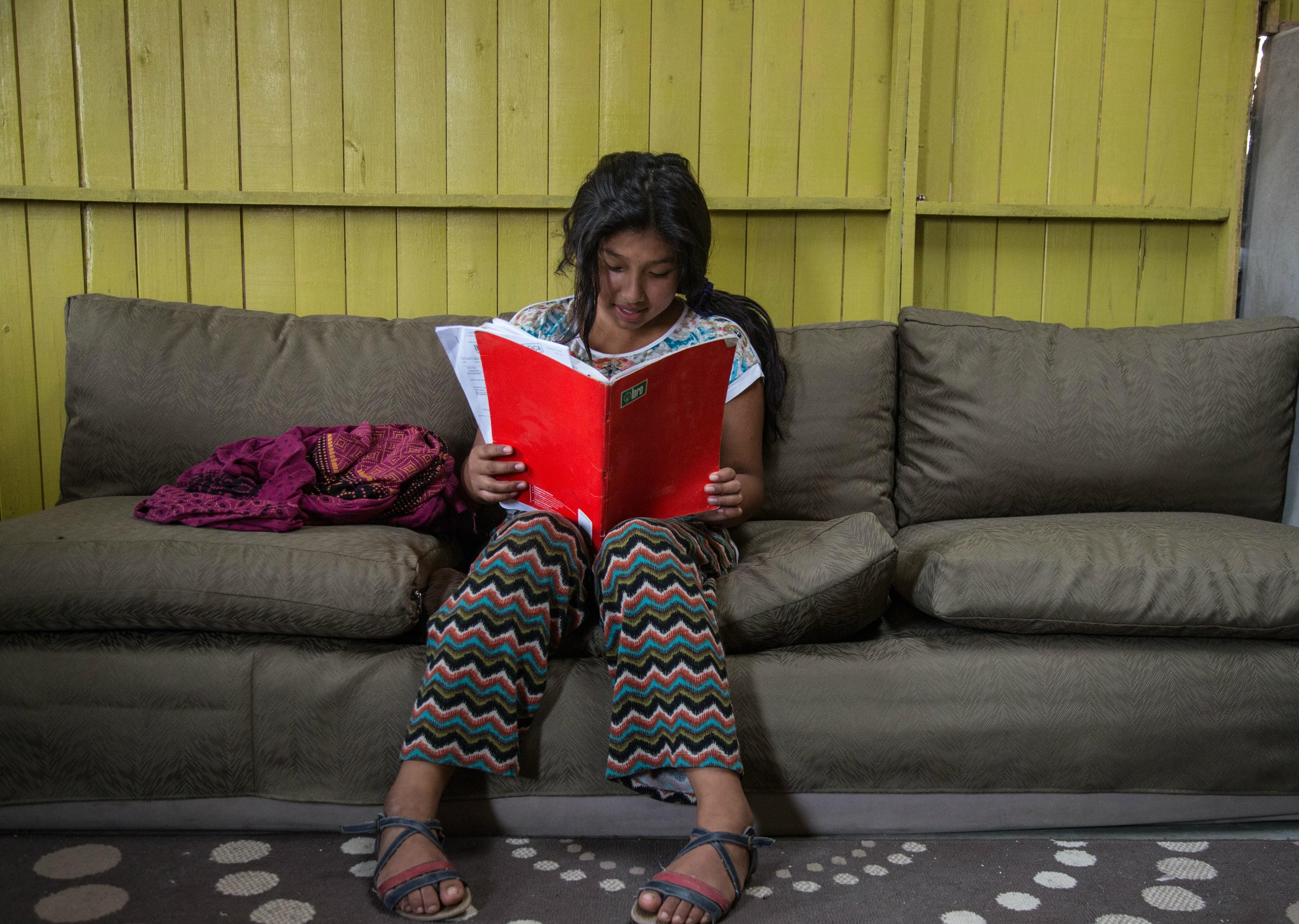

Forthcoming analysis of learning outcomes for Young Lives children from age 5 to 19 years indicates that educational outcomes (in maths and receptive vocabulary) for boys and girls show few signs of systematic bias at primary school age. However, gender gaps are frequently prominent after the age of 12 – the period coinciding with adolescence and post-primary schooling – and these gaps often persist into adulthood. In Ethiopia, India and Peru, girls are typically disadvantaged by these gender gaps. These findings indicate that interventions seeking to reduce gender gaps in eventual cognitive outcomes may best be targeted around the age of 12 to 15 years.

A wider perspective on marginalisation in education

Young Lives findings clearly indicate that girls are often marginalised from education, particularly at secondary level. However, Young Lives evidence also reveals that girls are not the only marginalised group within the poorest communities. Moreover, marginalisation and exclusion can be most serious where there are intersections between gender, poverty status, ethnicity, language and caste. For example, in Peru, a third of the children enrolled in school are over-age for the grade they are attending. However, there is little difference between the proportion of boys (30%) and girls (31%) who are left behind in their schooling. Instead, poverty and mothers’ education are more significantly associated with educational disadvantage; half the children from the poorest households or those whose mothers who had little education are over-age for their grade in the Young Lives sample.

In India, Young Lives evidence points to the potential reproduction of social inequalities in household education decisions, with families choosing to enrol their sons in private schools rather than their daughters. By contrast, in Vietnam, gender does not seem to influence parents’ level of investment in their children’s education. In the Young Lives sample, 63% of boys and 66% of girls were attending private tuition or extra classes in 2013. It is children from poorer and rural backgrounds who are excluded from these extra classes in Vietnam, with only 38% of children from the poorest families (compared to 86% from the richest families) and 59% of children from rural households (compared to 85% from urban households) attending extra classes.

In Vietnam, there is virtually no gender gap in enrolment at age 12, with 97.3% of boys and 97.8% of girls attending school. By contrast, a significant enrolment gap exists according to ethnicity, with 99% of Kinh majority children but only 88% of ethnic minority children attending school at age 12. A gender gap does emerge in terms of learning outcomes in Vietnam, but it is girls who perform better than boys, both in Vietnamese reading at primary level and in maths and receptive vocabulary at ages 12 to 15.

In both Ethiopia and Vietnam, the poorest boys are less likely to be enrolled in school at age 19 when compared to the poorest girls. In rural Ethiopia, boys typically spend more time doing paid work or working on the family farm or business, and so tend to drop out earlier than girls. By contrast, girls can be more flexible in combining study with responsibilities such as caring for others and domestic tasks, and are therefore more likely to stay in education after the age of 15.

Overall, evidence from Young Lives indicates that education policy and programmes must be responsive to the direction of gender gaps that emerge in schooling, as well as to the intersections of gender, ethnicity, language, caste, and geographical location that lead to the marginalisation and exclusion of young people from education.

The new Young Lives research and policy findings on early marriage and teenage pregnancy launched in India this week have important implications for education, particularly for girls and their access to secondary schooling.

In light of my own research interests in gender, sexuality and education in India, this week’s reports encouraged me to explore Young Lives’ wider findings on gender and education more closely. This post is an attempt to briefly summarise the evidence from Young Lives on gender and education, both in terms of girls’ marginalisation in education, and the study’s findings which indicate that we must think more broadly about gender and education – for example, by considering educational disadvantage linked to intersections between gender, poverty status, language, ethnicity, caste, and geographical location.

Girls’ marginalisation in education

Within the Young Lives sample in Andhra Pradesh and Telangana, India, girls are significantly less likely than boys to complete secondary education; only 66% of girls progress through secondary school, compared to 77% of boys. Findings from Young Lives qualitative research highlight many reasons for girls being marginalised in and excluded from secondary education, including distance to school, inadequate safety, and engagement in paid and unpaid labour, particularly after they attain puberty. These issues particularly affect girls from scheduled caste, scheduled tribe and ‘backward caste’ families.

The latest findings from Young Lives indicate that leaving school early is a powerful predictor of child marriage and early childbearing in India. In Andhra Pradesh and Telangana, girls in the Young Lives Older Cohort who left school by age 15 were four times more likely to marry before age 18 than girls who were still enrolled. These girls were also more likely to come from poorer households, and their parents and caregivers were less likely to be well-educated or to have high aspirations for their daughters. These findings indicate the importance of safe, accessible and high-quality secondary education for girls, as well as the need for effective social protection and investment in livelihoods and opportunities for young women and men, so families feel confident that they can delay their daughters’ marriage and invest in their education and future.

Child marriage also has implications for girls’ education in Ethiopia. Within the Young Lives Older Cohort, girls in rural Ethiopia are much more likely to marry than girls in cities, with 21% in rural areas married before the age of 18, compared to 3% in urban areas. In a context of few other opportunities, where girls’ education is limited and there are restricted chances of training or employment, early marriage may be viewed as a rational option by parents and sometimes by girls themselves. Early marriage is also often perceived as a ‘safe’ choice - in Young Lives sites many parents expressed anxieties about girls going to secondary schools far away from home, where they were perceived to be at greater risk of abduction or rape. However, education itself has also become an important force for change in reducing early marriage in Ethiopia, along with greater employment opportunities and higher aspirations of girls and their families.

Forthcoming analysis of learning outcomes for Young Lives children from age 5 to 19 years indicates that educational outcomes (in maths and receptive vocabulary) for boys and girls show few signs of systematic bias at primary school age. However, gender gaps are frequently prominent after the age of 12 – the period coinciding with adolescence and post-primary schooling – and these gaps often persist into adulthood. In Ethiopia, India and Peru, girls are typically disadvantaged by these gender gaps. These findings indicate that interventions seeking to reduce gender gaps in eventual cognitive outcomes may best be targeted around the age of 12 to 15 years.

A wider perspective on marginalisation in education

Young Lives findings clearly indicate that girls are often marginalised from education, particularly at secondary level. However, Young Lives evidence also reveals that girls are not the only marginalised group within the poorest communities. Moreover, marginalisation and exclusion can be most serious where there are intersections between gender, poverty status, ethnicity, language and caste. For example, in Peru, a third of the children enrolled in school are over-age for the grade they are attending. However, there is little difference between the proportion of boys (30%) and girls (31%) who are left behind in their schooling. Instead, poverty and mothers’ education are more significantly associated with educational disadvantage; half the children from the poorest households or those whose mothers who had little education are over-age for their grade in the Young Lives sample.

In India, Young Lives evidence points to the potential reproduction of social inequalities in household education decisions, with families choosing to enrol their sons in private schools rather than their daughters. By contrast, in Vietnam, gender does not seem to influence parents’ level of investment in their children’s education. In the Young Lives sample, 63% of boys and 66% of girls were attending private tuition or extra classes in 2013. It is children from poorer and rural backgrounds who are excluded from these extra classes in Vietnam, with only 38% of children from the poorest families (compared to 86% from the richest families) and 59% of children from rural households (compared to 85% from urban households) attending extra classes.

In Vietnam, there is virtually no gender gap in enrolment at age 12, with 97.3% of boys and 97.8% of girls attending school. By contrast, a significant enrolment gap exists according to ethnicity, with 99% of Kinh majority children but only 88% of ethnic minority children attending school at age 12. A gender gap does emerge in terms of learning outcomes in Vietnam, but it is girls who perform better than boys, both in Vietnamese reading at primary level and in maths and receptive vocabulary at ages 12 to 15.

In both Ethiopia and Vietnam, the poorest boys are less likely to be enrolled in school at age 19 when compared to the poorest girls. In rural Ethiopia, boys typically spend more time doing paid work or working on the family farm or business, and so tend to drop out earlier than girls. By contrast, girls can be more flexible in combining study with responsibilities such as caring for others and domestic tasks, and are therefore more likely to stay in education after the age of 15.

Overall, evidence from Young Lives indicates that education policy and programmes must be responsive to the direction of gender gaps that emerge in schooling, as well as to the intersections of gender, ethnicity, language, caste, and geographical location that lead to the marginalisation and exclusion of young people from education.