COVID-19 has inflicted significant economic and social impacts on young people. The Young Lives COVID-19 phone survey series, which started with three calls during 2020 with young people in Ethiopia, India, Peru and Vietnam, found that the pandemic is widening inequalities. Part of Young Lives 20 year longitudinal study, the phone survey found that the pandemic is also reversing progress towards the Sustainable Development Goals, with the combined pressures of interrupted education and increased domestic work and childcare having a disproportionate impact on vulnerable girls and young women.

The latest call interviewing just under 9,000 young people (from two birth cohorts and now aged 20 and 27) was a short, keeping-in-touch-call in August 2021 (Call 4). Designed to check in on our participants, and collect some basic information around vaccination, location, and a roster of household members, this short set of questions revealed three striking patterns, one of which was expected, two were more surprising. We set these out in this blog.

First, something that is sadly predictable: access to Covid-19 vaccinations is unequal both between and within our study countries, with the poorest households least likely to be vaccinated. Second, and more surprising, is the diverse trends in migration of young people in three of our countries. Finally, we find a welcome continuation of some positive long term trends: declining early marriage and teenage pregnancies, improving antenatal care and child health and nutrition. However, these may be under threat from the ongoing economic and social impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic.

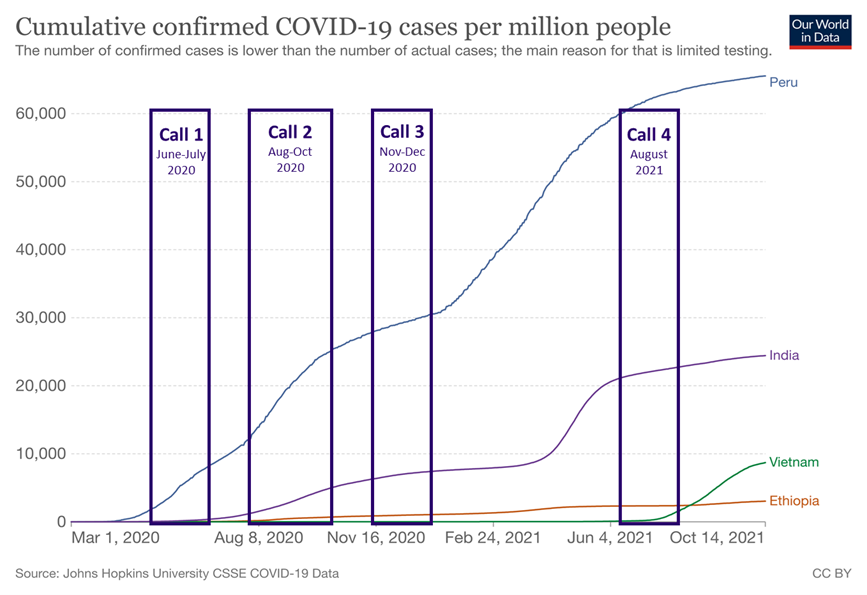

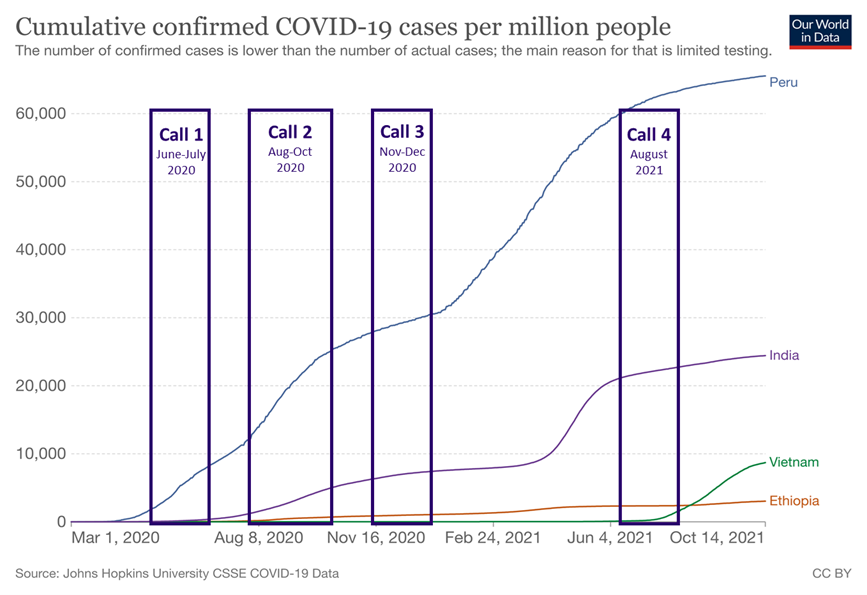

Our four study countries continue to have diverse experiences of the pandemic (see Figure 1). In August 2021, Peru still had one of the highest per capita Covid-19 deaths in the world, while Ethiopia and Vietnam had among the lowest. In all four countries, the main roll-out of vaccinations began between January 2021 and August 2021.

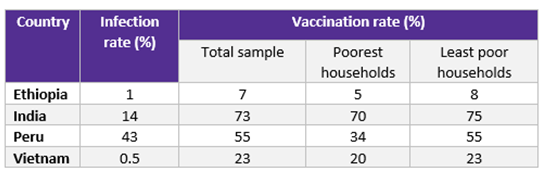

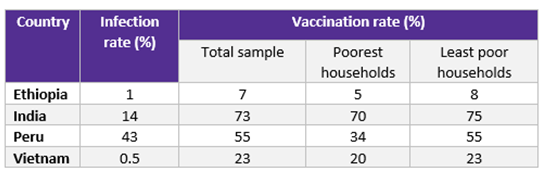

Our data tell a similar story, with huge variation in household infection rates (see Table 1): A very high proportion of Peruvian youth live in a household where someone has been infected (43%), followed by India (14%), but very low proportions in Ethiopia (1%), and Vietnam (0.5%).

In India, we note the highest percentage of vaccinated participants, at 34%, with lower rates in Vietnam (12%), Peru (7%), and Ethiopia (1%). In comparison, as of 26 August, roughly 72% of 18-24 years in England had received at least one dose – a rate more than two times higher than we observe in India and more than 70 times higher than in Ethiopia.

We found stark differences in vaccine access both between and within the four study countries. India had by far the highest vaccination rate, with 73% of Young Lives participants living in households with at least one vaccinated adult (received at least one dose); compared to 54% in Peru, 23% in Vietnam, and only 7% in Ethiopia.

Within all four countries, the poorest households were least likely to have at least one vaccinated adult. This was particularly pronounced in Peru, which had a 20-percentage point gap between the poorest and richest households.

To get a better understanding of how the pandemic may be affecting levels of migration, we compared our Younger Cohort (YC) who are now aged 19/20 to our Older Cohort (OC) when they were roughly the same age in 2013. This shows that migration was significantly higher during the pandemic in Peru (28% in 2021 vs 15% in 2013), where infection rates continue to be substantially higher than the other three study countries. In complete contrast, migration rates were much lower in Ethiopia (10% in 2021 vs 24% in 2013) and India (13% vs 35%), suggesting different factors at play that we will further research.

By comparison, there was no significant difference in patterns of migration in Vietnam, where infection rates were very low though interestingly Vietnam has the highest rate of migration overall, with over a third (36%) of young people moving to a new location (for at least one month, excluding holiday trips)

Table 1. Covid-19 infection and vaccination of households (Call 4 data August 2021

Whilst we have documented many worrying trends during the course of the pandemic, our longitudinal data tell us that some positive long-term trends seen over the last two decades have not yet been lost.

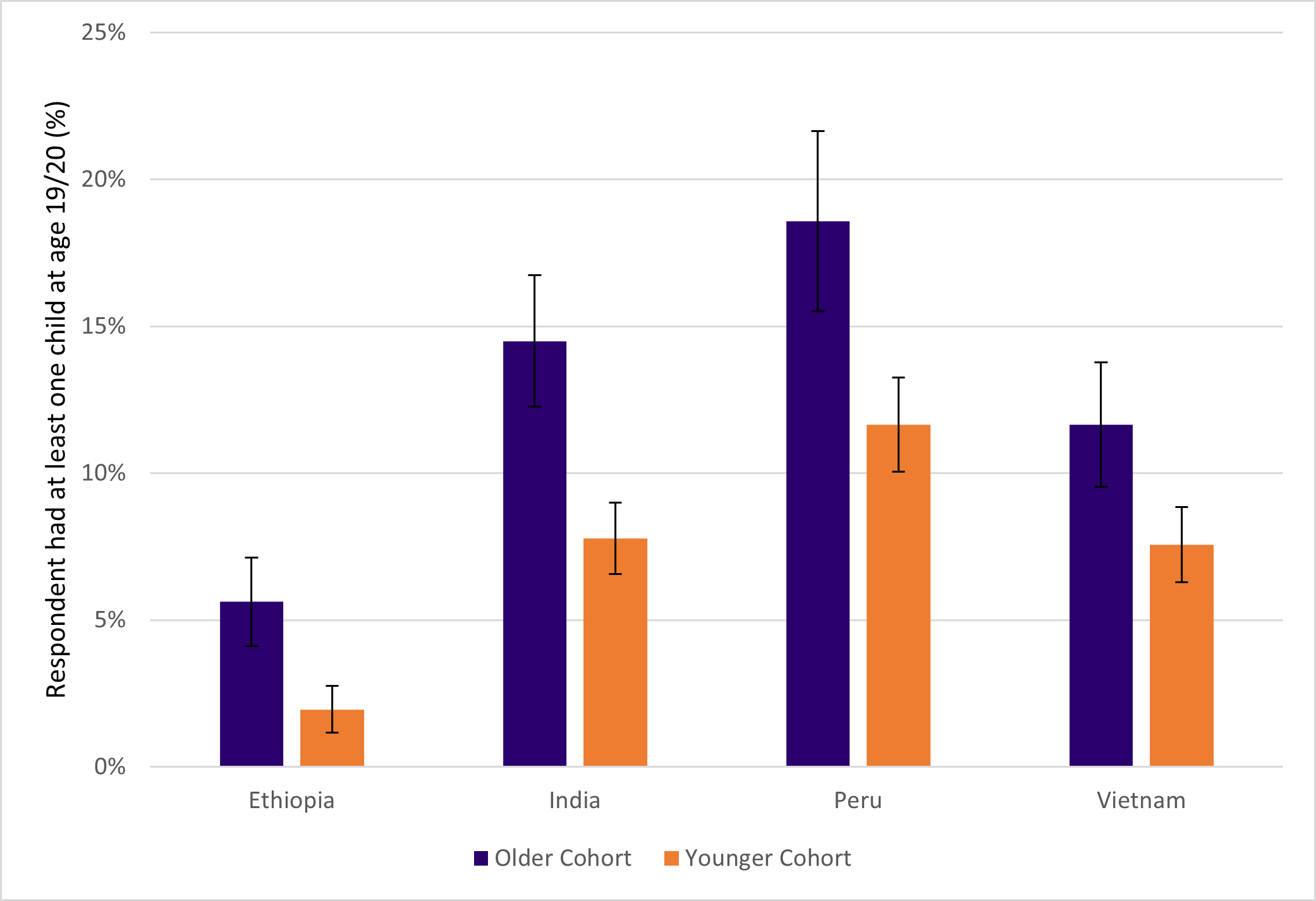

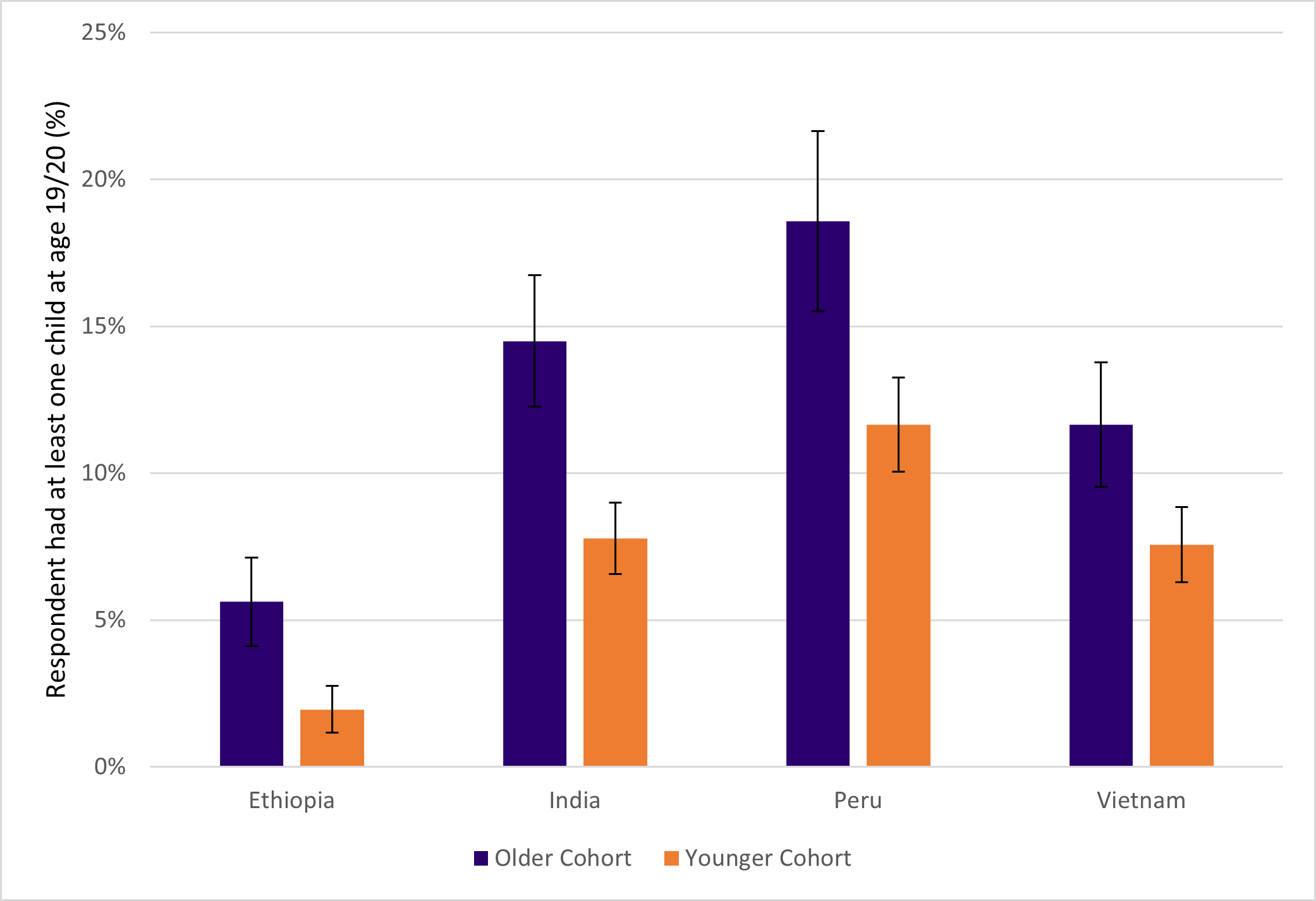

Encouragingly, data from our ‘getting in touch’ call indicates a continuing trend in lower rates of teenage pregnancy across all four countries (see Figure 2). By again comparing fertility rates of our Younger Cohort with the Older Cohort in 2013, we can see that the number of 19/20-year-olds with at least one child has continued to fall, ranging from only 2% in Ethiopia, up to 12% in Peru. Similarly, the proportion of 19/20-year-olds who are married or cohabitating declined in recent years, with only up to 15% (India) now married or cohabitating, compared to 20% in 2013.

Figure 2. Percentage of 19/20 year olds with at least one child in 2013 vs 2021

We turn now to the children of “our” children. Comparing birth circumstances of the children of our respondents with their parents when we measured them at the start of the Young Lives study 20 years ago, we note several positive trends. Importantly in India, the proportion of female babies has increased significantly from 46% to 50%, suggesting the phenomenon of “missing women” may be declining. There has been a significant improvement in access to antenatal care and having a skilled health personnel in attendance during labour across all four countries (now above 90%). In Ethiopia, having a skilled health personnel in attendance increased dramatically: from 17% in 2002 to 94% in 2021. We have also seen a corresponding increase in the birthweight of babies in India, Peru, and Vietnam.

Despite this positive news, we are concerned that increasing levels of food insecurity and mental health issues during the pandemic may undermine these improvements. Our evidence shows that malnutrition increases the risk of growth stunting, with long term consequences for cognitive skills and learning in school.

While more research is needed, we have found tentative evidence that care during pregnancy has been negatively affected during the pandemic. In Peru, children born during the pandemic received significantly fewer antenatal visits than those born before the pandemic.

Further, there remains a substantial gender bias in the age of both marriage and childbirth. Young women at age 20 are up to fifty times more likely to be married or cohabitating, or to have at least one child, than young men.

Previous Young Lives research has shown that early marriage is often seen as a way out of poverty in times of economic stress, especially in rural areas and among poorer households. Future research will determine the medium-term impact of the Covid-19 pandemic on these trends. The combined pressures of widespread stresses on household finances, with interrupted education and increased domestic work, may not only slow progress but may actually reverse trends, particularly for vulnerable girls and women in the poorest and most marginalised households.

Young Lives fieldworkers are currently busy collecting data in our next phone call survey from which we will publish key findings in March 2022. This more comprehensive survey, including employment, education, and physical and mental health, will enable us to better understand the medium-term economic and social impacts of the pandemic on young people, two years on from the start of the crisis.

COVID-19 has inflicted significant economic and social impacts on young people. The Young Lives COVID-19 phone survey series, which started with three calls during 2020 with young people in Ethiopia, India, Peru and Vietnam, found that the pandemic is widening inequalities. Part of Young Lives 20 year longitudinal study, the phone survey found that the pandemic is also reversing progress towards the Sustainable Development Goals, with the combined pressures of interrupted education and increased domestic work and childcare having a disproportionate impact on vulnerable girls and young women.

The latest call interviewing just under 9,000 young people (from two birth cohorts and now aged 20 and 27) was a short, keeping-in-touch-call in August 2021 (Call 4). Designed to check in on our participants, and collect some basic information around vaccination, location, and a roster of household members, this short set of questions revealed three striking patterns, one of which was expected, two were more surprising. We set these out in this blog.

First, something that is sadly predictable: access to Covid-19 vaccinations is unequal both between and within our study countries, with the poorest households least likely to be vaccinated. Second, and more surprising, is the diverse trends in migration of young people in three of our countries. Finally, we find a welcome continuation of some positive long term trends: declining early marriage and teenage pregnancies, improving antenatal care and child health and nutrition. However, these may be under threat from the ongoing economic and social impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Our four study countries continue to have diverse experiences of the pandemic (see Figure 1). In August 2021, Peru still had one of the highest per capita Covid-19 deaths in the world, while Ethiopia and Vietnam had among the lowest. In all four countries, the main roll-out of vaccinations began between January 2021 and August 2021.

Our data tell a similar story, with huge variation in household infection rates (see Table 1): A very high proportion of Peruvian youth live in a household where someone has been infected (43%), followed by India (14%), but very low proportions in Ethiopia (1%), and Vietnam (0.5%).

In India, we note the highest percentage of vaccinated participants, at 34%, with lower rates in Vietnam (12%), Peru (7%), and Ethiopia (1%). In comparison, as of 26 August, roughly 72% of 18-24 years in England had received at least one dose – a rate more than two times higher than we observe in India and more than 70 times higher than in Ethiopia.

We found stark differences in vaccine access both between and within the four study countries. India had by far the highest vaccination rate, with 73% of Young Lives participants living in households with at least one vaccinated adult (received at least one dose); compared to 54% in Peru, 23% in Vietnam, and only 7% in Ethiopia.

Within all four countries, the poorest households were least likely to have at least one vaccinated adult. This was particularly pronounced in Peru, which had a 20-percentage point gap between the poorest and richest households.

To get a better understanding of how the pandemic may be affecting levels of migration, we compared our Younger Cohort (YC) who are now aged 19/20 to our Older Cohort (OC) when they were roughly the same age in 2013. This shows that migration was significantly higher during the pandemic in Peru (28% in 2021 vs 15% in 2013), where infection rates continue to be substantially higher than the other three study countries. In complete contrast, migration rates were much lower in Ethiopia (10% in 2021 vs 24% in 2013) and India (13% vs 35%), suggesting different factors at play that we will further research.

By comparison, there was no significant difference in patterns of migration in Vietnam, where infection rates were very low though interestingly Vietnam has the highest rate of migration overall, with over a third (36%) of young people moving to a new location (for at least one month, excluding holiday trips)

Table 1. Covid-19 infection and vaccination of households (Call 4 data August 2021

Whilst we have documented many worrying trends during the course of the pandemic, our longitudinal data tell us that some positive long-term trends seen over the last two decades have not yet been lost.

Encouragingly, data from our ‘getting in touch’ call indicates a continuing trend in lower rates of teenage pregnancy across all four countries (see Figure 2). By again comparing fertility rates of our Younger Cohort with the Older Cohort in 2013, we can see that the number of 19/20-year-olds with at least one child has continued to fall, ranging from only 2% in Ethiopia, up to 12% in Peru. Similarly, the proportion of 19/20-year-olds who are married or cohabitating declined in recent years, with only up to 15% (India) now married or cohabitating, compared to 20% in 2013.

Figure 2. Percentage of 19/20 year olds with at least one child in 2013 vs 2021

We turn now to the children of “our” children. Comparing birth circumstances of the children of our respondents with their parents when we measured them at the start of the Young Lives study 20 years ago, we note several positive trends. Importantly in India, the proportion of female babies has increased significantly from 46% to 50%, suggesting the phenomenon of “missing women” may be declining. There has been a significant improvement in access to antenatal care and having a skilled health personnel in attendance during labour across all four countries (now above 90%). In Ethiopia, having a skilled health personnel in attendance increased dramatically: from 17% in 2002 to 94% in 2021. We have also seen a corresponding increase in the birthweight of babies in India, Peru, and Vietnam.

Despite this positive news, we are concerned that increasing levels of food insecurity and mental health issues during the pandemic may undermine these improvements. Our evidence shows that malnutrition increases the risk of growth stunting, with long term consequences for cognitive skills and learning in school.

While more research is needed, we have found tentative evidence that care during pregnancy has been negatively affected during the pandemic. In Peru, children born during the pandemic received significantly fewer antenatal visits than those born before the pandemic.

Further, there remains a substantial gender bias in the age of both marriage and childbirth. Young women at age 20 are up to fifty times more likely to be married or cohabitating, or to have at least one child, than young men.

Previous Young Lives research has shown that early marriage is often seen as a way out of poverty in times of economic stress, especially in rural areas and among poorer households. Future research will determine the medium-term impact of the Covid-19 pandemic on these trends. The combined pressures of widespread stresses on household finances, with interrupted education and increased domestic work, may not only slow progress but may actually reverse trends, particularly for vulnerable girls and women in the poorest and most marginalised households.

Young Lives fieldworkers are currently busy collecting data in our next phone call survey from which we will publish key findings in March 2022. This more comprehensive survey, including employment, education, and physical and mental health, will enable us to better understand the medium-term economic and social impacts of the pandemic on young people, two years on from the start of the crisis.