Internationally, education has been heralded as a key instrument for individual and national development. How much has been accomplished towards realising the goal of quality education for all is a matter of debate and research. Recently a series of nineteen volumes has been planned to overview recent research for every region in the world. The series is edited by Colin Brook of the University of Durham and published by Bloomsbury. The most recently (fourth) published volume focuses on Education in South America, edited by Simon Schwartzman, and prompted these reflections.

Evident progress and challenges

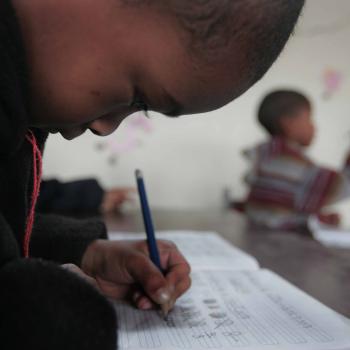

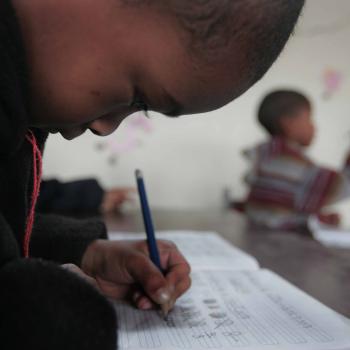

The volume on South America includes 19 chapters on Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Ecuador, Paraguay, Peru, Uruguay and Venezuela. All chapters were written by local researchers or policymakers (I co-wrote the chapter on Peru). The data shows in many cases that there has been progress in education over the past few decades; for example, coverage in primary education is above 90% for most countries (Bolivia and Paraguay lagging slightly behind). Literacy has also increased, with rates above 90%. In addition, public investment in education has been growing in the region,

However, the volume also shows that the scores of children participating in various international testing programs (e.g. PISA) lag behind those of industrialised countries; furthermore, sometimes the scores are lower than those of developing countries in other regions with comparable economic indicators. The tests also show that within countries, there are often wide variations, which are associated with individual and family variables, including poverty and ethnicity (achieving effective intercultural bilingual education remains a challenge for many countries in SA). Understanding why we have this combination of low quality and high inequality, in results and opportunities, is crucial for moving forward. Our own Young Lives research strongly supports this.

Main issues in debate

There are several issues that run through many chapters. The first one is governance. Many countries in the region have issued a national agreement, long-term plan, or new national laws attempting to reform the whole system or some part of it (e.g. teachers’ policies). It seems however that the implementation of these instruments varies, with serious doubts that any top-down approaches in policy may be successful. Also related to governance, many countries in the region have seen an advancement in the offer of private education. Whether or not this may lead to segregation and further inequality is an issue with only some data (e.g. Chile). Finally, in regards to governance, many countries have started or reformed their decentralisation in education regulations. It seems obvious even in the more experienced countries (like Brazil) that there are yet many challenges associated with making decentralisation a relevant instrument for educational quality for all.

A second issue discussed in several chapters is teachers. Several countries have started or reformed their teacher training programmes, which traditionally were associated with experience on the job. The new programmes have attempted to lure more skilled young students, evaluate in-service teachers, and retain those that show better performance, tying skills and performance to pay increases (e.g. Chile). However, many challenges remain as to how to raise the quality of teachers, pedagogical processes in classrooms, and incorporate effectively new technologies, which in some countries have been adopted massively (e.g. Uruguay).

Scope of the book and ways to move forward

By design, the book deals only with basic education. Most chapters refer to primary education,

Finally, now that coverage in higher education (post-secondary) is increasing in all South American countries, (though there are many questions regarding its quality), as a next step, a similar volume on higher education in the region would be very relevant.

Internationally, education has been heralded as a key instrument for individual and national development. How much has been accomplished towards realising the goal of quality education for all is a matter of debate and research. Recently a series of nineteen volumes has been planned to overview recent research for every region in the world. The series is edited by Colin Brook of the University of Durham and published by Bloomsbury. The most recently (fourth) published volume focuses on Education in South America, edited by Simon Schwartzman, and prompted these reflections.

Evident progress and challenges

The volume on South America includes 19 chapters on Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Ecuador, Paraguay, Peru, Uruguay and Venezuela. All chapters were written by local researchers or policymakers (I co-wrote the chapter on Peru). The data shows in many cases that there has been progress in education over the past few decades; for example, coverage in primary education is above 90% for most countries (Bolivia and Paraguay lagging slightly behind). Literacy has also increased, with rates above 90%. In addition, public investment in education has been growing in the region,

However, the volume also shows that the scores of children participating in various international testing programs (e.g. PISA) lag behind those of industrialised countries; furthermore, sometimes the scores are lower than those of developing countries in other regions with comparable economic indicators. The tests also show that within countries, there are often wide variations, which are associated with individual and family variables, including poverty and ethnicity (achieving effective intercultural bilingual education remains a challenge for many countries in SA). Understanding why we have this combination of low quality and high inequality, in results and opportunities, is crucial for moving forward. Our own Young Lives research strongly supports this.

Main issues in debate

There are several issues that run through many chapters. The first one is governance. Many countries in the region have issued a national agreement, long-term plan, or new national laws attempting to reform the whole system or some part of it (e.g. teachers’ policies). It seems however that the implementation of these instruments varies, with serious doubts that any top-down approaches in policy may be successful. Also related to governance, many countries in the region have seen an advancement in the offer of private education. Whether or not this may lead to segregation and further inequality is an issue with only some data (e.g. Chile). Finally, in regards to governance, many countries have started or reformed their decentralisation in education regulations. It seems obvious even in the more experienced countries (like Brazil) that there are yet many challenges associated with making decentralisation a relevant instrument for educational quality for all.

A second issue discussed in several chapters is teachers. Several countries have started or reformed their teacher training programmes, which traditionally were associated with experience on the job. The new programmes have attempted to lure more skilled young students, evaluate in-service teachers, and retain those that show better performance, tying skills and performance to pay increases (e.g. Chile). However, many challenges remain as to how to raise the quality of teachers, pedagogical processes in classrooms, and incorporate effectively new technologies, which in some countries have been adopted massively (e.g. Uruguay).

Scope of the book and ways to move forward

By design, the book deals only with basic education. Most chapters refer to primary education,

Finally, now that coverage in higher education (post-secondary) is increasing in all South American countries, (though there are many questions regarding its quality), as a next step, a similar volume on higher education in the region would be very relevant.