Why do some children fare well in the face of adversity?

Why do some children growing up in poverty seem to fare well, despite the odds being stacked against them early in life? BBC Ideas has teamed up with Oxford University's Social Science Division to make four short films about big research ideas. We're delighted that Young Lives research on what it takes for children to fare well features in one of these amazing short films.

Growing up in poverty, the children in our study have had to navigate many challenges all of which can tip life chances in profound ways – both positive or negative.

Using Young Lives' household survey data, Gina Crivello and Ginny Morrow selected children who had experienced many difficulties yet nevertheless appeared to be doing well in their early 20’s to find out what works. In their research paper 'Against the Odds: Why Some Children Fare Well in the Face of Adversity' they identified a set of factors that helped children and young people navigate life's challenges well.

They found that an individual's character counts; children who fared well were positive, self-motivated, and believed they could succeed despite life's obstacle, but this was not enough. To do well, children needed wider support from relationships within or outside their family, and the help of government safety nets and community projects supporting their family. Social values that supported their hopes and dreams and a second chance to get back on track also mattered.

Children were able to beat the odds when they were supported by others from within and outside the family. Elder siblings and other young relatives can influence children to fare well.

Mulu grew up in a poor household in a rural community in Ethiopia's Amhara region. At just nine years old her father died leaving the family in financial difficulty. A year later, Mulu started work picking coffee, and later, haricot beans for cash alongside attending school and doing housework. This was difficult to manage, but Mulu reasoned that earning money helped her family and paid for her schooling. Mulu’s elder sister joined college, moving four years later to a job in town from where she sent money home. Her sister's leaving meant more housework for Mulu but passing the national Grade 10 exam strengthened Mulu’s resolve to continue studying and when her elder sister lobbied their mother to allow her to she moved to town to study. Living with her elder sister in town, Mulu completed university and is now working as a civil engineer.

Government and NGO’s support to bolster poor families against shocks helps children fare well. Many children told Young Lives that if their household received such support it helped their families through difficult periods.

Over the last two decades, Young Lives evidence has shown that government safety nets, in the form of social protection programmes such as the PSNP in Ethiopia and JUNTOS in Peru, can deliver wide ranging benefits for disadvantaged children, particularly in relation to their growth and nutrition. Our new research shows – for the first time – that this support can also have a positive impact on their early cognitive skills development, such as better long-term memory and implicit learning, the building blocks for later life learning.

Sarada grew up in a village with her family who belonged to a low-caste community. She was an ambitious child but a physical disability meant she could only walk short distances, and couldn't stand for any length of time. When their house collapsed the family took out a loan to build a new house and Sarada and her younger siblings were taken out of school to work to pay off the debt. However, against her parents’ will, Sarada insisted on going to school, and the local self-help group, the Disabled People’s Association, provided her with financial support, enabling her to continue into secondary school.

Aged 20, Sarada was two years into her degree and teaching part-time in a night school with the ambition to become a professionally qualified teacher. The Disabled People’s Association had not only directly supported her, it also provided a source of informal support, empowering her to challenge her parents when they wanted her to work instead of going to school.

Several children spoke of second chances that were particularly crucial during turning points, such as with parental death or exam failure. Second chances were not random, however, and children were not passive in responding to them. It was necessary that children had the inclination to take advantage of such opportunities. Second chances had the power to shift children’s trajectories in differing ways. They helped children return to a ‘pathway’ they may never have wanted to leave in the first place, and offered a renewed sense of hope.

In India, Rajesh, spoke throughout his childhood of education as the route to success. Initially very ambitious, his aims dwindled from age 12 (‘I want to be a doctor’) to age 20 (‘whichever job I get fastest, that one I will take … It depends on fate’). His family were very poor; an illness meant he changed school age 13; aged 17 he had a motorbike accident and his father fell ill; his family took on debts to pay for his sister’s undergraduate degree. By age 19, he had moved to a nearby town for two months’ training as a security guard, and then was sent to Chennai to work. However, after a year, he returned to the village – he had been working at night but was very homesick.

By age 20, he was living in his village, supporting his family, and had returned to education. His elder sisters (both teachers) made most of the decisions in the household, and they encouraged him throughout his childhood to study. By age 22, Rajesh spent most of his time attending college.

Social values that legitimated girls’ and boys’ school participation were key, although the realities of poverty made it difficult to always live up to them.

Over time, as children grew up they become more aware of structural inequalities. Maria (from Peru), echoing her mother, said living in a ‘machista’ society made it important for her to gain financial independence through a profession. Many of the girls who aspired to professional careers knew of young women either from their communities or ‘like them’ who were already working in their desired professions.

Children said that community level development helped their households and their future prospects. For example, the introduction of electricity helped because it meant they could study at night. And the switch from rain fed to irrigation agriculture was key for rural boys in Ethiopia as a major positive change that enabled them to earn more and stay on the family farm.

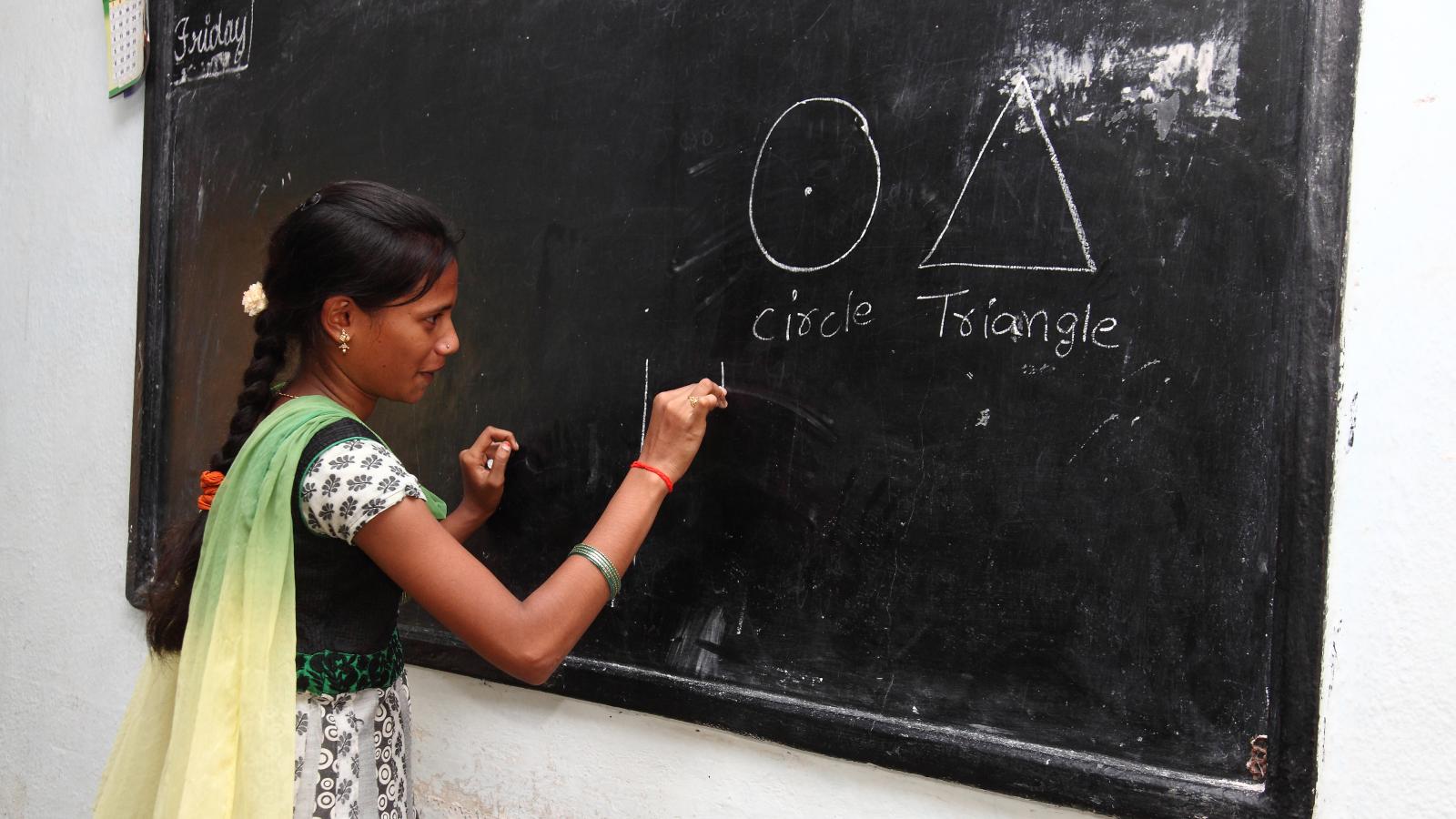

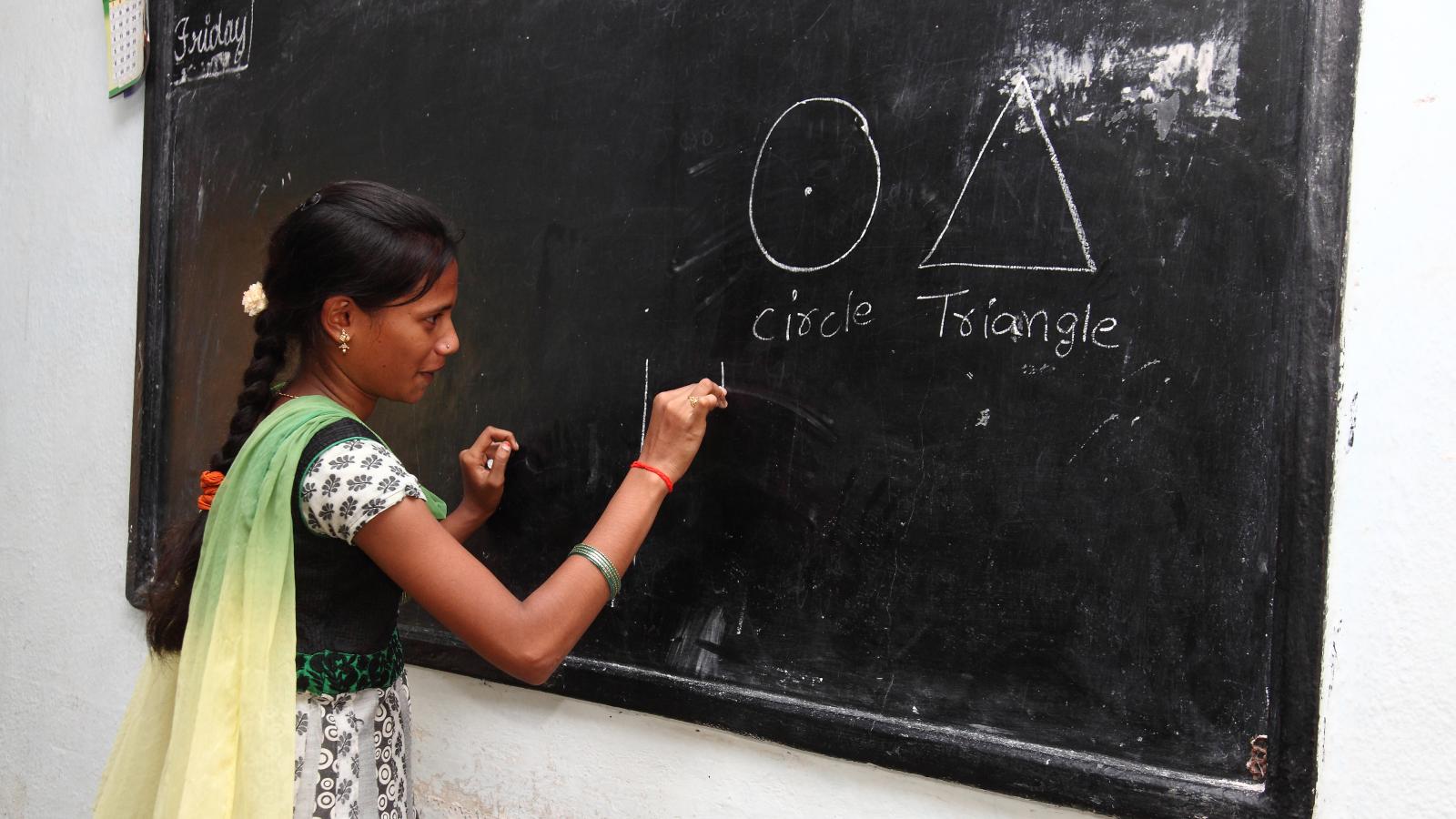

Children were also able to fare well when there were positive enabling environments in their homes, schools and communities. An enabling home was one with enough food for everyone, and where families were able to relieve children and young people from paid and unpaid work to focus on studying. A school environment with teachers sympathetic to the pressures on children helped; for example understanding when they were unable to afford school-related costs or when they missed school due to personal or family illness and for seasonal work.

The pieces of Young Lives research referenced in the BBC Ideas film are

Gina Crivello & Virginia Morrow (2020) Against the Odds: Why Some Children Fare Well in the Face of Adversity, the Journal of Development Studies, 56:5, 999-1016

Scott, D., J. Lopez, A. Sánchez and J. R. Behrman (2022) ‘The impact of the JUNTOS conditional cash transfer programme on foundational cognitive skills: Does age of enrolment matter?’ https://economics.sas.upenn.edu/pier/working-paper/2022/impact-juntos-conditional-cash-transfer-programme-foundational-cognitive

Freund, R., M. Favara, C. Porter and J. Berhman (2022) ‘Social protection and foundational cognitive skills during adolescence: evidence from a large Public Works Programme’ https://economics.sas.upenn.edu/pier/working-paper/2022/social-protection-and-foundational-cognitive-skills-during-adolescence

It is with great sadness that Gina Crivello passed away in April 2022. You can read more about her work here.

Why do some children fare well in the face of adversity?

Why do some children growing up in poverty seem to fare well, despite the odds being stacked against them early in life? BBC Ideas has teamed up with Oxford University's Social Science Division to make four short films about big research ideas. We're delighted that Young Lives research on what it takes for children to fare well features in one of these amazing short films.

Growing up in poverty, the children in our study have had to navigate many challenges all of which can tip life chances in profound ways – both positive or negative.

Using Young Lives' household survey data, Gina Crivello and Ginny Morrow selected children who had experienced many difficulties yet nevertheless appeared to be doing well in their early 20’s to find out what works. In their research paper 'Against the Odds: Why Some Children Fare Well in the Face of Adversity' they identified a set of factors that helped children and young people navigate life's challenges well.

They found that an individual's character counts; children who fared well were positive, self-motivated, and believed they could succeed despite life's obstacle, but this was not enough. To do well, children needed wider support from relationships within or outside their family, and the help of government safety nets and community projects supporting their family. Social values that supported their hopes and dreams and a second chance to get back on track also mattered.

Children were able to beat the odds when they were supported by others from within and outside the family. Elder siblings and other young relatives can influence children to fare well.

Mulu grew up in a poor household in a rural community in Ethiopia's Amhara region. At just nine years old her father died leaving the family in financial difficulty. A year later, Mulu started work picking coffee, and later, haricot beans for cash alongside attending school and doing housework. This was difficult to manage, but Mulu reasoned that earning money helped her family and paid for her schooling. Mulu’s elder sister joined college, moving four years later to a job in town from where she sent money home. Her sister's leaving meant more housework for Mulu but passing the national Grade 10 exam strengthened Mulu’s resolve to continue studying and when her elder sister lobbied their mother to allow her to she moved to town to study. Living with her elder sister in town, Mulu completed university and is now working as a civil engineer.

Government and NGO’s support to bolster poor families against shocks helps children fare well. Many children told Young Lives that if their household received such support it helped their families through difficult periods.

Over the last two decades, Young Lives evidence has shown that government safety nets, in the form of social protection programmes such as the PSNP in Ethiopia and JUNTOS in Peru, can deliver wide ranging benefits for disadvantaged children, particularly in relation to their growth and nutrition. Our new research shows – for the first time – that this support can also have a positive impact on their early cognitive skills development, such as better long-term memory and implicit learning, the building blocks for later life learning.

Sarada grew up in a village with her family who belonged to a low-caste community. She was an ambitious child but a physical disability meant she could only walk short distances, and couldn't stand for any length of time. When their house collapsed the family took out a loan to build a new house and Sarada and her younger siblings were taken out of school to work to pay off the debt. However, against her parents’ will, Sarada insisted on going to school, and the local self-help group, the Disabled People’s Association, provided her with financial support, enabling her to continue into secondary school.

Aged 20, Sarada was two years into her degree and teaching part-time in a night school with the ambition to become a professionally qualified teacher. The Disabled People’s Association had not only directly supported her, it also provided a source of informal support, empowering her to challenge her parents when they wanted her to work instead of going to school.

Several children spoke of second chances that were particularly crucial during turning points, such as with parental death or exam failure. Second chances were not random, however, and children were not passive in responding to them. It was necessary that children had the inclination to take advantage of such opportunities. Second chances had the power to shift children’s trajectories in differing ways. They helped children return to a ‘pathway’ they may never have wanted to leave in the first place, and offered a renewed sense of hope.

In India, Rajesh, spoke throughout his childhood of education as the route to success. Initially very ambitious, his aims dwindled from age 12 (‘I want to be a doctor’) to age 20 (‘whichever job I get fastest, that one I will take … It depends on fate’). His family were very poor; an illness meant he changed school age 13; aged 17 he had a motorbike accident and his father fell ill; his family took on debts to pay for his sister’s undergraduate degree. By age 19, he had moved to a nearby town for two months’ training as a security guard, and then was sent to Chennai to work. However, after a year, he returned to the village – he had been working at night but was very homesick.

By age 20, he was living in his village, supporting his family, and had returned to education. His elder sisters (both teachers) made most of the decisions in the household, and they encouraged him throughout his childhood to study. By age 22, Rajesh spent most of his time attending college.

Social values that legitimated girls’ and boys’ school participation were key, although the realities of poverty made it difficult to always live up to them.

Over time, as children grew up they become more aware of structural inequalities. Maria (from Peru), echoing her mother, said living in a ‘machista’ society made it important for her to gain financial independence through a profession. Many of the girls who aspired to professional careers knew of young women either from their communities or ‘like them’ who were already working in their desired professions.

Children said that community level development helped their households and their future prospects. For example, the introduction of electricity helped because it meant they could study at night. And the switch from rain fed to irrigation agriculture was key for rural boys in Ethiopia as a major positive change that enabled them to earn more and stay on the family farm.

Children were also able to fare well when there were positive enabling environments in their homes, schools and communities. An enabling home was one with enough food for everyone, and where families were able to relieve children and young people from paid and unpaid work to focus on studying. A school environment with teachers sympathetic to the pressures on children helped; for example understanding when they were unable to afford school-related costs or when they missed school due to personal or family illness and for seasonal work.

The pieces of Young Lives research referenced in the BBC Ideas film are

Gina Crivello & Virginia Morrow (2020) Against the Odds: Why Some Children Fare Well in the Face of Adversity, the Journal of Development Studies, 56:5, 999-1016

Scott, D., J. Lopez, A. Sánchez and J. R. Behrman (2022) ‘The impact of the JUNTOS conditional cash transfer programme on foundational cognitive skills: Does age of enrolment matter?’ https://economics.sas.upenn.edu/pier/working-paper/2022/impact-juntos-conditional-cash-transfer-programme-foundational-cognitive

Freund, R., M. Favara, C. Porter and J. Berhman (2022) ‘Social protection and foundational cognitive skills during adolescence: evidence from a large Public Works Programme’ https://economics.sas.upenn.edu/pier/working-paper/2022/social-protection-and-foundational-cognitive-skills-during-adolescence

It is with great sadness that Gina Crivello passed away in April 2022. You can read more about her work here.