Violent conflicts are on the rise globally, with incidences increasing by 22% from 2019 to 2023, and 1 in 6 people exposed to conflict in 2024, according to the ACLED Conflict Index. Amid this escalating violence, high-quality research is crucial to get behind the headlines and understand the full impact of conflict on individuals and communities, informing effective peacebuilding and reconstruction policies, and supporting those most affected. But collecting accurate data on the experiences of people caught up in conflict can be very challenging. Traumatised respondents may be reluctant to open up and special care is required to ensure they feel as safe as possible during the survey process.

This blog describes how Young Lives has addressed some of these challenges by piloting the use of innovative audio computer-assisted self-interviews (ACASI) to collect information about young people’s experiences of violent conflict in Ethiopia. This approach not only prioritizes the well-being of survey respondents, but also enhances data accuracy, helping us to better understand how conflict has impacted individuals and their communities.

While ACASI has previously been shown to increase the disclosure of drug use, sexual behaviour, adverse mental health, and intimate partner violence, we are, to the best of our knowledge, the first study to assess its added value for collecting personal experiences in a conflict setting.

Gathering quality data during conflicts can be challenging

When fighting broke out in Ethiopia’s Tigray region in November 2020, Young Lives was the only longitudinal study able to continue collecting data through our COVID-19 phone survey. This survey highlighted some of the early impacts of the conflict, revealing the dramatic situation our respondents in Tigray were experiencing, particularly evident in rapidly deteriorating mental health. However, as the violence escalated and communication channels were disrupted towards the end of 2021, we were forced to pause data collection in conflict-affected areas.

Not surprisingly, collecting high-quality data either during or in the aftermath of armed conflict can be very challenging. Safety concerns, destroyed roads, disrupted communications and movement restrictions make it very difficult to reach respondents, both in-person or over the phone. Longitudinal studies, in particular, face challenges tracking their participants due to conflict-induced displacement or forced migration.

Protecting survey respondents from experiencing further trauma is paramount

Even when interviews are possible, asking about traumatic conflict experiences can retraumatize respondents, because it requires them to relive difficult and sensitive experiences. This can also be upsetting for the fieldworkers and researchers involved, who can also suffer secondary trauma in the process.

In face-to-face quantitative interviews, data quality can suffer due to risks of misreporting or underreporting, as respondents may feel ashamed of their experiences of physical or sexual violence, fear stigmatization by the interviewer, or worry about negative consequences if their answers became public.

Safeguarding the well-being of survey respondents and maintaining a duty of care towards them is paramount for all data collection activities in conflict areas. Young Lives is committed to upholding the highest ethical standards, and considers research ethics as integral to the success of the study and the generation of reliable, high-quality data. Our use of ACASI in response to the recent armed conflict in Ethiopia is a testament to this commitment and has contributed to the successful collection of important new data, despite the challenging environment.

Piloting audio computer-assisted self-interviews (ACASI) in Ethiopia

Following the peace agreement in November 2022, we conducted a short pilot survey in May 2023 to evaluate the use of ACASI, which we specifically designed to ask highly sensitive questions about the impact of conflict, as well as personal experiences of different types of violence, drug and alcohol use, and sexual and reproductive health. The pilot involved interviewing 139 young people from 10 sites close to our main Young Lives sample, representing similar social and economic backgrounds.

ACASI prioritises duty of care

ACASI allows respondents to answer questions using pre-programmed tablets and headphones, by listening to (rather than reading) simple yes or no questions, and responding by touching coloured shapes on the tablet screen, as shown below. The process of responding in private and without an interviewer’s involvement is designed to minimise distress when recalling traumatic events and to eliminate the risk of anyone overhearing the answers.

The audio function is particularly important in Ethiopia where many of our study participants have low levels of literacy. Our survey questions were translated into three local languages and recorded by both male and female speakers, to match respondents’ ethnicity and gender identity.

Individuals are more likely to report conflict experiences using ACASI

To test the effectiveness and accuracy of using ACASI, respondents were randomly allocated either to answer nine questions about the impact of conflict as part of our usual face-to-face interview (the control group), or to answer the same questions using ACASI. The randomization ensured that respondents in the control group had similar background characteristics to those using ACASI, including an equal proportion of respondents from conflict-affected regions. This was done to ensure that both groups had a similar likelihood of having been exposed to conflict situations.

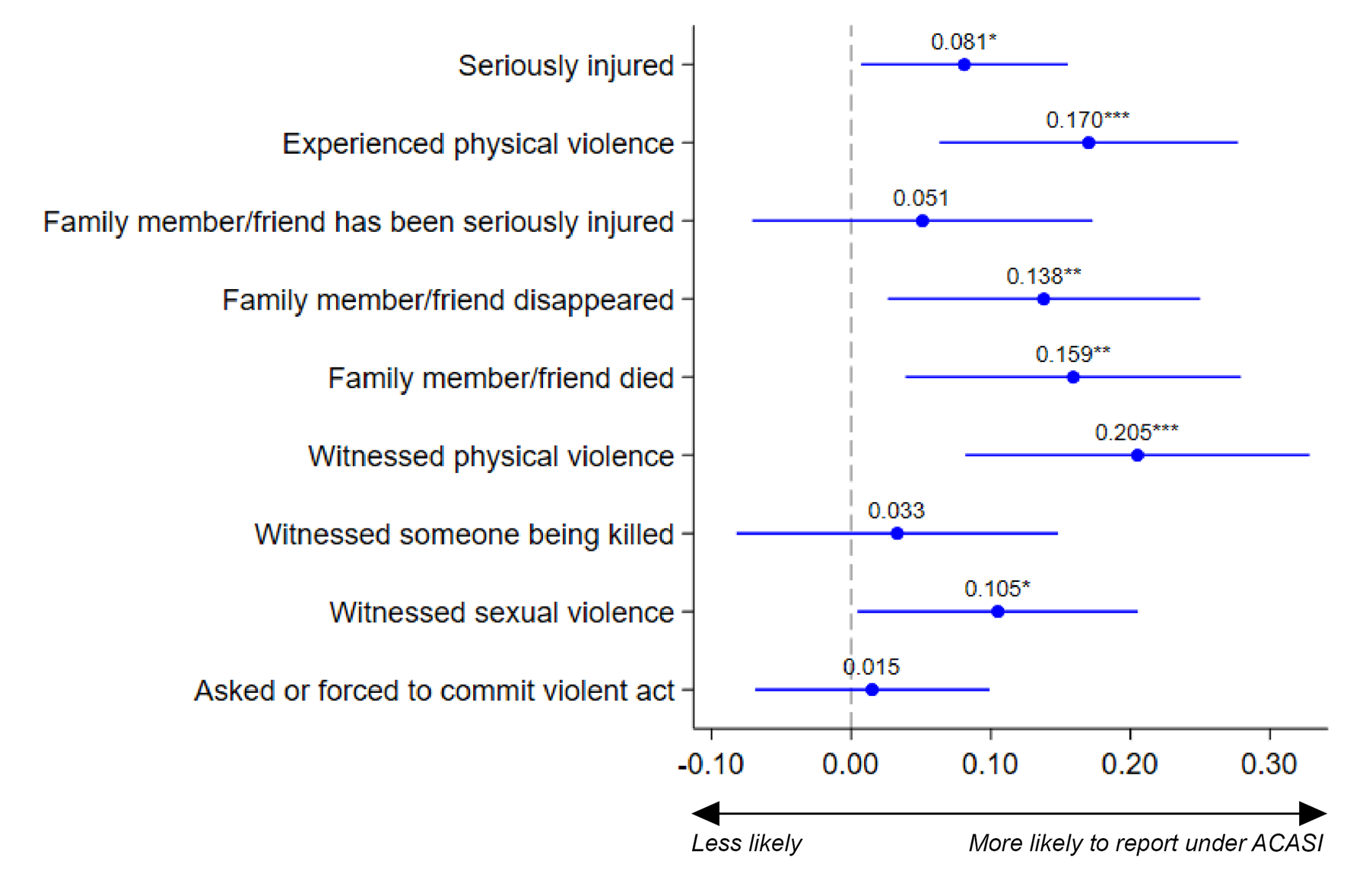

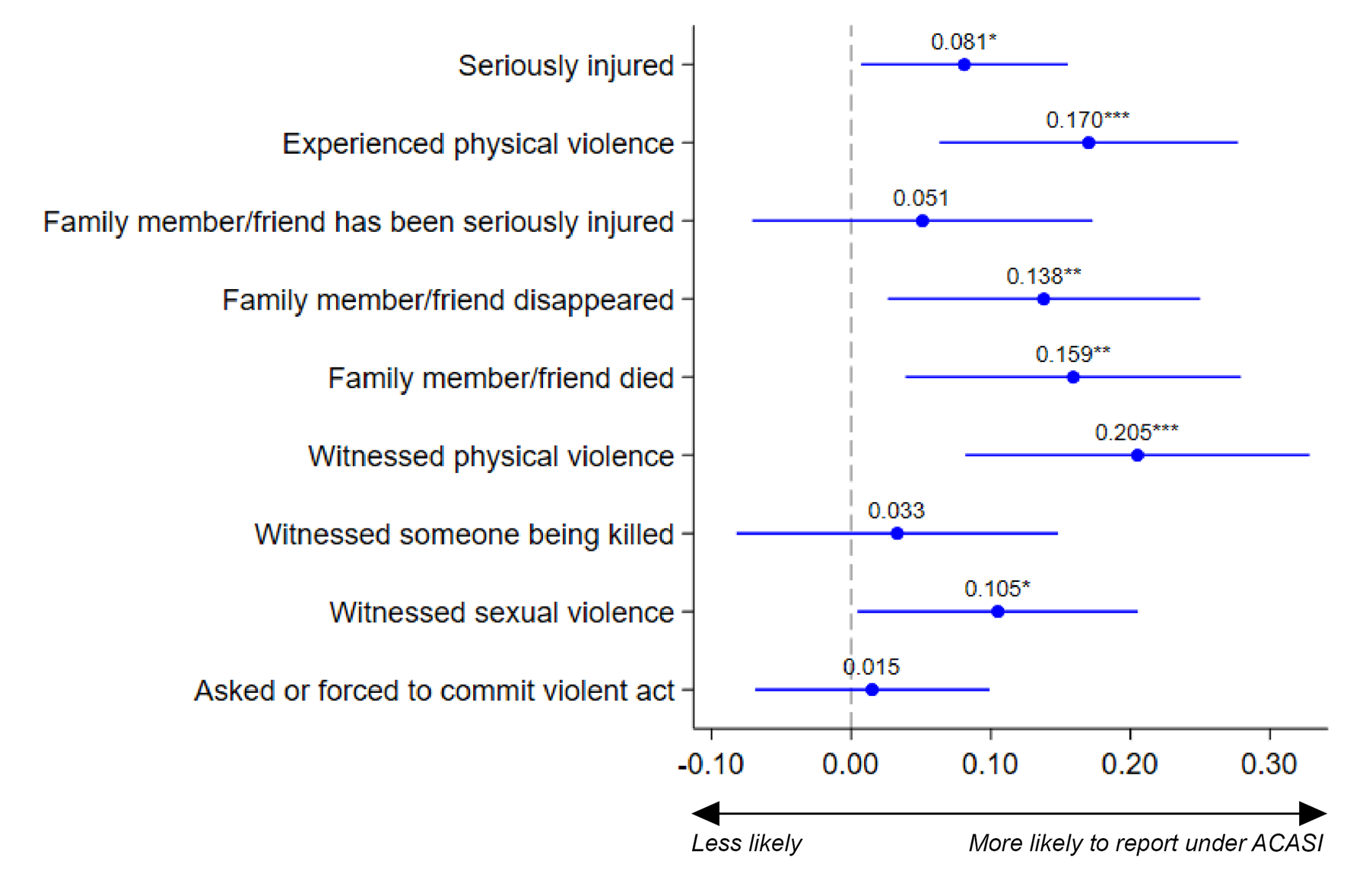

By comparing data collected from respondents using ACASI with the control group, we found that individuals are significantly more likely to report conflict experiences using ACASI compared to face-to-face interviews. On average, respondents reported one additional conflict experience (out of nine categories) when using ACASI and were 18 percentage points more likely to report at least one conflict experience.

Moreover, respondents were more likely to report conflict experiences involving themselves as victims when using ACASI, compared to face-to-face interviews. We also saw increased reporting using ACASI when the experiences were more severe, or when incidents involved family members or friends, as shown in the graph below. For example, respondents were 20.5 percentage points more likely to report witnessing physical violence using ACASI than in face-to-face interviews.

ACASI has its limitations but offers huge potential when carefully implemented

Although using ACASI can reduce underreporting of conflict experiences, it does have some limitations compared to face-to-face interviews. Firstly, the provision of tablets and headphones, and recording questions in multiple languages and using male and female speakers, can be costly and time-consuming. Secondly, although ACASI does not require respondents to have reading skills, using tablets requires a certain level of digital literacy and clear instructions from fieldworkers, who will themselves require specific training.

Despite these limitations, when ACASI is correctly and carefully implemented, it can provide a valuable addition to effective survey design in conflict-settings. Even in very challenging circumstances, this approach not only prioritises duty of care to reduce vulnerable respondents’ exposure to stress and risks, but it also enhances researchers’ ability to accurately collect high quality data.

The conflict is having a devastating impact on young people

While our pilot survey focused on testing the validity and robustness of ACASI, it also revealed the devastating impacts of conflict on young people in Ethiopia. We found shocking levels of physical and sexual violence, with 60% of young people in Tigray participating in our pilot reporting that a friend or family member had been seriously injured, had disappeared, or had died as a result of the conflict, and 29% in Amhara stating they had witnessed sexual violence. Additionally, many young people have faced significant personal and economic shocks, such as the inability to find or continue work, running out of food, forced migration and displacement, and the disruption of markets due to the conflict.

Looking forward

Our pilot survey concluded that ACASI was successfully implemented, addressing concerns about underreporting and ensuring proper duty of care. Based on these results, Young Lives subsequently used ACASI to collect information on young people’s conflict experiences across our whole Ethiopian sample in our Round 7 survey, completed in May 2024 with remarkably low attrition rates. In-person data collection using ACASI was successfully conducted in all our 20 Ethiopia sites, except for two sites in the Amhara region where ongoing fighting necessitated a phone survey. We are now beginning to analyse this data to better understand how the conflict is affecting the lives of young people and their families, and to identify where support is most needed. Young Lives plans to publish findings from Round 7 in 2025.

This blog is based on the paper “A sound methodology: Measuring experiences of violent conflict through audio self-interviews” by Sophie von Russdorf, Marta Favara, Laura Ahlborn, Alessandra Hidalgo-Arestegui, and Gerald McQuade, Economic Letters X:X (2024).

Violent conflicts are on the rise globally, with incidences increasing by 22% from 2019 to 2023, and 1 in 6 people exposed to conflict in 2024, according to the ACLED Conflict Index. Amid this escalating violence, high-quality research is crucial to get behind the headlines and understand the full impact of conflict on individuals and communities, informing effective peacebuilding and reconstruction policies, and supporting those most affected. But collecting accurate data on the experiences of people caught up in conflict can be very challenging. Traumatised respondents may be reluctant to open up and special care is required to ensure they feel as safe as possible during the survey process.

This blog describes how Young Lives has addressed some of these challenges by piloting the use of innovative audio computer-assisted self-interviews (ACASI) to collect information about young people’s experiences of violent conflict in Ethiopia. This approach not only prioritizes the well-being of survey respondents, but also enhances data accuracy, helping us to better understand how conflict has impacted individuals and their communities.

While ACASI has previously been shown to increase the disclosure of drug use, sexual behaviour, adverse mental health, and intimate partner violence, we are, to the best of our knowledge, the first study to assess its added value for collecting personal experiences in a conflict setting.

Gathering quality data during conflicts can be challenging

When fighting broke out in Ethiopia’s Tigray region in November 2020, Young Lives was the only longitudinal study able to continue collecting data through our COVID-19 phone survey. This survey highlighted some of the early impacts of the conflict, revealing the dramatic situation our respondents in Tigray were experiencing, particularly evident in rapidly deteriorating mental health. However, as the violence escalated and communication channels were disrupted towards the end of 2021, we were forced to pause data collection in conflict-affected areas.

Not surprisingly, collecting high-quality data either during or in the aftermath of armed conflict can be very challenging. Safety concerns, destroyed roads, disrupted communications and movement restrictions make it very difficult to reach respondents, both in-person or over the phone. Longitudinal studies, in particular, face challenges tracking their participants due to conflict-induced displacement or forced migration.

Protecting survey respondents from experiencing further trauma is paramount

Even when interviews are possible, asking about traumatic conflict experiences can retraumatize respondents, because it requires them to relive difficult and sensitive experiences. This can also be upsetting for the fieldworkers and researchers involved, who can also suffer secondary trauma in the process.

In face-to-face quantitative interviews, data quality can suffer due to risks of misreporting or underreporting, as respondents may feel ashamed of their experiences of physical or sexual violence, fear stigmatization by the interviewer, or worry about negative consequences if their answers became public.

Safeguarding the well-being of survey respondents and maintaining a duty of care towards them is paramount for all data collection activities in conflict areas. Young Lives is committed to upholding the highest ethical standards, and considers research ethics as integral to the success of the study and the generation of reliable, high-quality data. Our use of ACASI in response to the recent armed conflict in Ethiopia is a testament to this commitment and has contributed to the successful collection of important new data, despite the challenging environment.

Piloting audio computer-assisted self-interviews (ACASI) in Ethiopia

Following the peace agreement in November 2022, we conducted a short pilot survey in May 2023 to evaluate the use of ACASI, which we specifically designed to ask highly sensitive questions about the impact of conflict, as well as personal experiences of different types of violence, drug and alcohol use, and sexual and reproductive health. The pilot involved interviewing 139 young people from 10 sites close to our main Young Lives sample, representing similar social and economic backgrounds.

ACASI prioritises duty of care

ACASI allows respondents to answer questions using pre-programmed tablets and headphones, by listening to (rather than reading) simple yes or no questions, and responding by touching coloured shapes on the tablet screen, as shown below. The process of responding in private and without an interviewer’s involvement is designed to minimise distress when recalling traumatic events and to eliminate the risk of anyone overhearing the answers.

The audio function is particularly important in Ethiopia where many of our study participants have low levels of literacy. Our survey questions were translated into three local languages and recorded by both male and female speakers, to match respondents’ ethnicity and gender identity.

Individuals are more likely to report conflict experiences using ACASI

To test the effectiveness and accuracy of using ACASI, respondents were randomly allocated either to answer nine questions about the impact of conflict as part of our usual face-to-face interview (the control group), or to answer the same questions using ACASI. The randomization ensured that respondents in the control group had similar background characteristics to those using ACASI, including an equal proportion of respondents from conflict-affected regions. This was done to ensure that both groups had a similar likelihood of having been exposed to conflict situations.

By comparing data collected from respondents using ACASI with the control group, we found that individuals are significantly more likely to report conflict experiences using ACASI compared to face-to-face interviews. On average, respondents reported one additional conflict experience (out of nine categories) when using ACASI and were 18 percentage points more likely to report at least one conflict experience.

Moreover, respondents were more likely to report conflict experiences involving themselves as victims when using ACASI, compared to face-to-face interviews. We also saw increased reporting using ACASI when the experiences were more severe, or when incidents involved family members or friends, as shown in the graph below. For example, respondents were 20.5 percentage points more likely to report witnessing physical violence using ACASI than in face-to-face interviews.

ACASI has its limitations but offers huge potential when carefully implemented

Although using ACASI can reduce underreporting of conflict experiences, it does have some limitations compared to face-to-face interviews. Firstly, the provision of tablets and headphones, and recording questions in multiple languages and using male and female speakers, can be costly and time-consuming. Secondly, although ACASI does not require respondents to have reading skills, using tablets requires a certain level of digital literacy and clear instructions from fieldworkers, who will themselves require specific training.

Despite these limitations, when ACASI is correctly and carefully implemented, it can provide a valuable addition to effective survey design in conflict-settings. Even in very challenging circumstances, this approach not only prioritises duty of care to reduce vulnerable respondents’ exposure to stress and risks, but it also enhances researchers’ ability to accurately collect high quality data.

The conflict is having a devastating impact on young people

While our pilot survey focused on testing the validity and robustness of ACASI, it also revealed the devastating impacts of conflict on young people in Ethiopia. We found shocking levels of physical and sexual violence, with 60% of young people in Tigray participating in our pilot reporting that a friend or family member had been seriously injured, had disappeared, or had died as a result of the conflict, and 29% in Amhara stating they had witnessed sexual violence. Additionally, many young people have faced significant personal and economic shocks, such as the inability to find or continue work, running out of food, forced migration and displacement, and the disruption of markets due to the conflict.

Looking forward

Our pilot survey concluded that ACASI was successfully implemented, addressing concerns about underreporting and ensuring proper duty of care. Based on these results, Young Lives subsequently used ACASI to collect information on young people’s conflict experiences across our whole Ethiopian sample in our Round 7 survey, completed in May 2024 with remarkably low attrition rates. In-person data collection using ACASI was successfully conducted in all our 20 Ethiopia sites, except for two sites in the Amhara region where ongoing fighting necessitated a phone survey. We are now beginning to analyse this data to better understand how the conflict is affecting the lives of young people and their families, and to identify where support is most needed. Young Lives plans to publish findings from Round 7 in 2025.

This blog is based on the paper “A sound methodology: Measuring experiences of violent conflict through audio self-interviews” by Sophie von Russdorf, Marta Favara, Laura Ahlborn, Alessandra Hidalgo-Arestegui, and Gerald McQuade, Economic Letters X:X (2024).