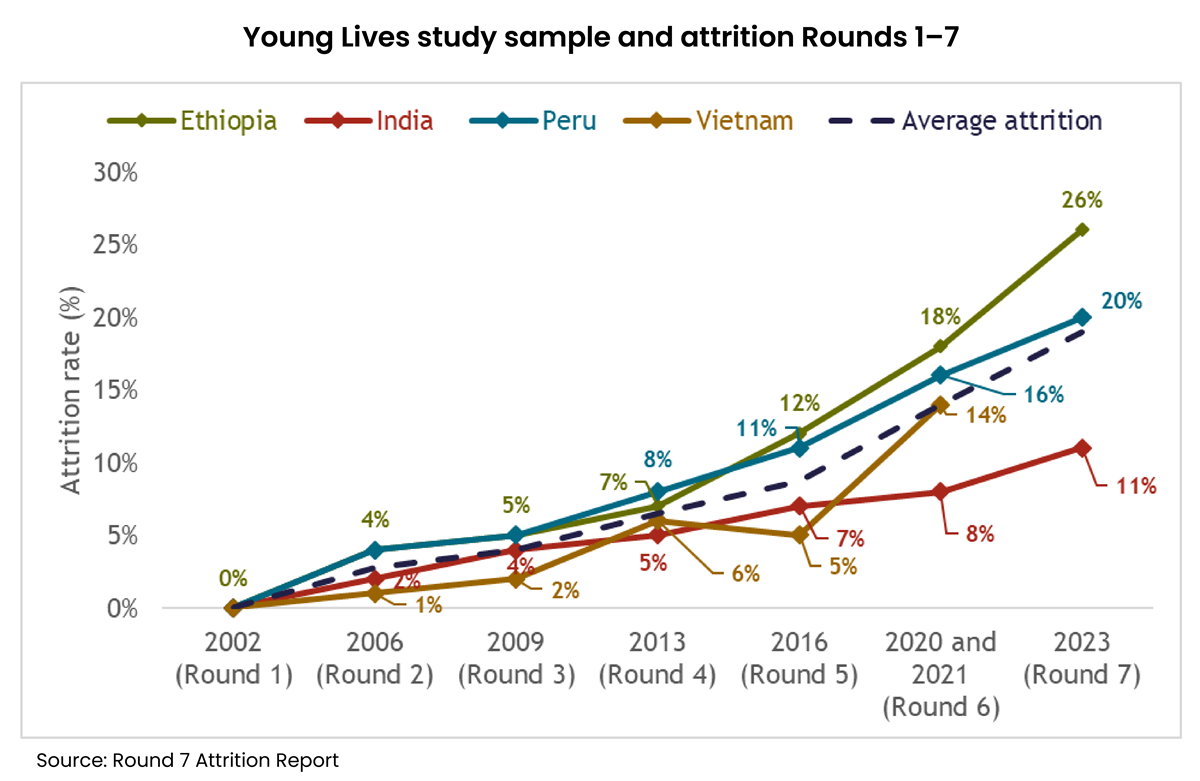

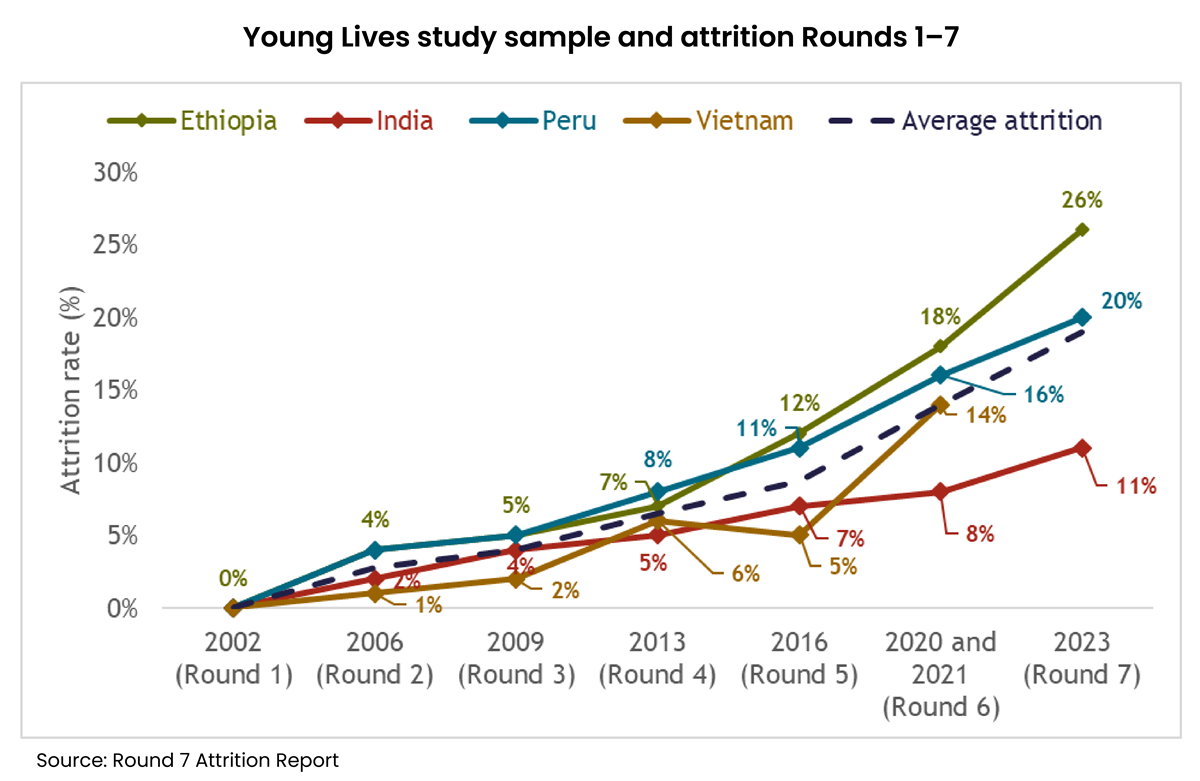

In 2023, Young Lives returned to in-person interviews, after a phone-based survey Round in 2020-21, and successfully completed the seventh round of data collection in Ethiopia, India (states of Telangana and Andhra Pradesh), and Peru. We are delighted to report that 21 years after the 1st survey round, we have retained just over eight out of ten of our original study participants, as documented in our Round 7 Attrition Report, just published.

Twenty-one years on from the first round of data collection in 2002, we tracked down and interviewed 81% of the original Young Lives participants. In other words, we have lost just 19% of the 2002 sample (attrition rate), equal to less than 1% a year - with some variation across countries (25.6% in Ethiopia, 11.5% in India, and 19.8% in Peru).

As Young Lives' participants have grown up it has become more complex to track their location in each survey round. When we first visited them in 2002, the Younger Cohort were aged 1 and the Older Cohort were 8 years old. By Round 7, they were 22 and 29 years old. Over time, and as they have left school, started work and formed families, it has become ever more challenging to locate them, in part because of both internal and international migration. Cohort maintenance is a key aim of any longitudinal study, and although tracking participants is a challenge, migration also provides potential opportunities for research. In this blog, we discuss some of the challenges we faced tracking our participants in Round 7, how we overcome these, and exciting new avenues of research.

Migration – both internal and international – is one of the main causes of attrition in longitudinal studies. Despite the increased mobility of Young Lives respondents in the past two survey rounds, the study has been extremely successful in minimising attrition. The study initially defined 20 sites (or clusters) per country from which to sample respondents, meaning that they were geographically contained. However, since the beginning, Young Lives decided to track participants migrating within the national borders (or state borders in the case of India), even if this included moving outside of the original 20 sites. Participants who migrated abroad (or outside the states of Andhra Pradesh and Telangana) were not followed. In 2002, respondents lived in 20 woredas in Ethiopia, 20 mandals in India and 27 districts in Peru; while in 2023, we had our participants spread in approximately 130 woredas, 306 mandals and 281 districts respectively.

Despite tracking only those participants who have moved within their own countries, this is still a demanding, and increasingly complex task. In Peru, many participants have migrated from rural to urban areas seeking better job or educational opportunities. However, during the pandemic many dropped out of their studies, or lost their jobs, and returned home. To minimise attrition in Round 7, and after completing the main fieldwork, Young Lives team in Peru team dedicated an extra month to search for migrants within national borders. In Ethiopia, the armed conflict in the north of the country increased the number of internally displaced people dramatically. In 2023, with the help of local guides, we identified and interviewed participants in person who had relocated to the capital due to the conflict in Amhara. To guarantee the safety of our participants and enumerators, we also conducted interviews by phone in two Amhara clusters.

In addition to the initiatives above, Young Lives has used three key strategies to keep attrition rates low and retain as many internal migrants as possible during the course of the study.

In each survey round, approximately six months before data collection starts, each country team conducts a preliminary tracking exercise to locate participants, update contact details, and inform participants about the upcoming data collection. The information collected is recorded using computer-assisted personal interviewing (CAPI), as in the main survey rounds, and allows enumerators to plan the routes to take in the survey round proper.

Young Lives collects comprehensive contact details in each survey round including the telephone number of the respondents, caregivers, and close family members, detailed information on the place of residence, including full address and notes left by the enumerators to better locate the respondent's dwelling - particularly useful in rural and remote areas. The contact details and addresses are updated when we track participants at each survey round. Young Lives also collects the GPS location of the families, to facilitate future tracking.

- Many of the Young Lives enumerators have been with the study for a long period of time (in many cases since the first two survey rounds), and so they know the respondents, their families, the communities where they live, and the routes to access these communities, really well, which helps to facilitate the search for (and interactions with) the respondents.

Country teams track migrants in different ways. During each round, as well as visiting the original 20 clusters, enumerators also visit other geographical areas where Young Lives participants have migrated, according to the tracking information. This poses a challenge to our fieldwork teams, as they sometimes need to travel long distances or try to reach remote places. In certain cases, decisions are made not to visit participants in remote areas or who have migrated temporarily. To make the search for the participants who have migrated more efficient the fieldwork team contacts them beforehand and, in cases where they are living outside the sites, they try to group participants together to interview them in one go. Furthermore, the last weeks of fieldwork are dedicated to reaching those not found at the addresses provided during the tracking round or who could not be visited before for other reasons. For example, the Young Lives team in India takes advantage of public holidays, when they expect the participants to travel back to their hometowns, to meet with them and interview them in the original sites where their families are still living.

Although migration presents significant challenges during fieldwork, it also offers great potential for research.

Young Lives has consistently collected detailed data on participants’ household location in each round together with information on where they have lived between rounds. This enables us to reconstruct a participant’s migration history and look into the drivers of migration (including the role of shocks, such as climate crises, the COVID-19 pandemic or conflict) as well as the consequences of migration on health, nutrition, well-being, education, employment and family life outcomes of Young Lives participants.

As crises compound, understanding who migrates and who remains becomes increasingly important. In a longitudinal study such as Young Lives, assessing the characteristics of participants who have migrated, compared to those who have not, will continue to be a key area of research

Detailed information on participants’ location over time is extremely important for understanding better their exposure to local and global crises, including COVID-19, conflict and climate and environmental shocks. Currently, most evidence on the impact of climate and environmental shocks makes strong assumptions about migration patterns as this information is not typically observed by the researcher, making it very challenging to accurately analyse the impact of shocks when exposure occurred many years ago. The Young Lives' new Research Hub on Climate and Environmental Shocks will address this challenge by using granular location and migration data over the life course to identify the impacts of such shocks.

Finally, our team has been working hard to prepare the data from the seventh round of data collection. Fact sheets highlighting key findings on health and nutrition, education, work and family lives and a series of technical notes will be released soon.

In 2023, Young Lives returned to in-person interviews, after a phone-based survey Round in 2020-21, and successfully completed the seventh round of data collection in Ethiopia, India (states of Telangana and Andhra Pradesh), and Peru. We are delighted to report that 21 years after the 1st survey round, we have retained just over eight out of ten of our original study participants, as documented in our Round 7 Attrition Report, just published.

Twenty-one years on from the first round of data collection in 2002, we tracked down and interviewed 81% of the original Young Lives participants. In other words, we have lost just 19% of the 2002 sample (attrition rate), equal to less than 1% a year - with some variation across countries (25.6% in Ethiopia, 11.5% in India, and 19.8% in Peru).

As Young Lives' participants have grown up it has become more complex to track their location in each survey round. When we first visited them in 2002, the Younger Cohort were aged 1 and the Older Cohort were 8 years old. By Round 7, they were 22 and 29 years old. Over time, and as they have left school, started work and formed families, it has become ever more challenging to locate them, in part because of both internal and international migration. Cohort maintenance is a key aim of any longitudinal study, and although tracking participants is a challenge, migration also provides potential opportunities for research. In this blog, we discuss some of the challenges we faced tracking our participants in Round 7, how we overcome these, and exciting new avenues of research.

Migration – both internal and international – is one of the main causes of attrition in longitudinal studies. Despite the increased mobility of Young Lives respondents in the past two survey rounds, the study has been extremely successful in minimising attrition. The study initially defined 20 sites (or clusters) per country from which to sample respondents, meaning that they were geographically contained. However, since the beginning, Young Lives decided to track participants migrating within the national borders (or state borders in the case of India), even if this included moving outside of the original 20 sites. Participants who migrated abroad (or outside the states of Andhra Pradesh and Telangana) were not followed. In 2002, respondents lived in 20 woredas in Ethiopia, 20 mandals in India and 27 districts in Peru; while in 2023, we had our participants spread in approximately 130 woredas, 306 mandals and 281 districts respectively.

Despite tracking only those participants who have moved within their own countries, this is still a demanding, and increasingly complex task. In Peru, many participants have migrated from rural to urban areas seeking better job or educational opportunities. However, during the pandemic many dropped out of their studies, or lost their jobs, and returned home. To minimise attrition in Round 7, and after completing the main fieldwork, Young Lives team in Peru team dedicated an extra month to search for migrants within national borders. In Ethiopia, the armed conflict in the north of the country increased the number of internally displaced people dramatically. In 2023, with the help of local guides, we identified and interviewed participants in person who had relocated to the capital due to the conflict in Amhara. To guarantee the safety of our participants and enumerators, we also conducted interviews by phone in two Amhara clusters.

In addition to the initiatives above, Young Lives has used three key strategies to keep attrition rates low and retain as many internal migrants as possible during the course of the study.

In each survey round, approximately six months before data collection starts, each country team conducts a preliminary tracking exercise to locate participants, update contact details, and inform participants about the upcoming data collection. The information collected is recorded using computer-assisted personal interviewing (CAPI), as in the main survey rounds, and allows enumerators to plan the routes to take in the survey round proper.

Young Lives collects comprehensive contact details in each survey round including the telephone number of the respondents, caregivers, and close family members, detailed information on the place of residence, including full address and notes left by the enumerators to better locate the respondent's dwelling - particularly useful in rural and remote areas. The contact details and addresses are updated when we track participants at each survey round. Young Lives also collects the GPS location of the families, to facilitate future tracking.

- Many of the Young Lives enumerators have been with the study for a long period of time (in many cases since the first two survey rounds), and so they know the respondents, their families, the communities where they live, and the routes to access these communities, really well, which helps to facilitate the search for (and interactions with) the respondents.

Country teams track migrants in different ways. During each round, as well as visiting the original 20 clusters, enumerators also visit other geographical areas where Young Lives participants have migrated, according to the tracking information. This poses a challenge to our fieldwork teams, as they sometimes need to travel long distances or try to reach remote places. In certain cases, decisions are made not to visit participants in remote areas or who have migrated temporarily. To make the search for the participants who have migrated more efficient the fieldwork team contacts them beforehand and, in cases where they are living outside the sites, they try to group participants together to interview them in one go. Furthermore, the last weeks of fieldwork are dedicated to reaching those not found at the addresses provided during the tracking round or who could not be visited before for other reasons. For example, the Young Lives team in India takes advantage of public holidays, when they expect the participants to travel back to their hometowns, to meet with them and interview them in the original sites where their families are still living.

Although migration presents significant challenges during fieldwork, it also offers great potential for research.

Young Lives has consistently collected detailed data on participants’ household location in each round together with information on where they have lived between rounds. This enables us to reconstruct a participant’s migration history and look into the drivers of migration (including the role of shocks, such as climate crises, the COVID-19 pandemic or conflict) as well as the consequences of migration on health, nutrition, well-being, education, employment and family life outcomes of Young Lives participants.

As crises compound, understanding who migrates and who remains becomes increasingly important. In a longitudinal study such as Young Lives, assessing the characteristics of participants who have migrated, compared to those who have not, will continue to be a key area of research

Detailed information on participants’ location over time is extremely important for understanding better their exposure to local and global crises, including COVID-19, conflict and climate and environmental shocks. Currently, most evidence on the impact of climate and environmental shocks makes strong assumptions about migration patterns as this information is not typically observed by the researcher, making it very challenging to accurately analyse the impact of shocks when exposure occurred many years ago. The Young Lives' new Research Hub on Climate and Environmental Shocks will address this challenge by using granular location and migration data over the life course to identify the impacts of such shocks.

Finally, our team has been working hard to prepare the data from the seventh round of data collection. Fact sheets highlighting key findings on health and nutrition, education, work and family lives and a series of technical notes will be released soon.